DAVID SIMPSON

A CONVERSATION WITH DAVID SIMPSON

Interview by Dan Golden

David Simpson is a reductive painter who has been central to the Bay Area art scene since the 1950s. Working initially with materials that included metallic paints, and later with interference pigments, his paintings shimmer and alter in the light, depending on their angle of view. Simpson has exhibited his work widely since the 1950s, throughout Europe, Asia, and the United States. He is represented in public and private collections including the Panza Collection, Varese, Italy; the Museo Cantonale d’Arte, Lugano, Switzerland; the Museum of Modern Art, NY; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, CA; Philadelphia Museum of Art, PA; Seattle Museum of Art, WA; National Collection of Fine Art, Washington, DC; John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Chicago; and the Contemporary and Modern Art Museum of Trento and Rovereto, Italy. Simpson received his MFA from San Francisco State College (now SFSU) and BFA from the California School of Fine Arts (now San Francisco Art Institute).

Dan Golden: Congratulations on your recent show at Haines Gallery. I wish I had been out there to see it. It seemed like it was a really great retrospective.

David Simpson: Thank you. It was interesting to see paintings from the 1950s, for instance, and even the '70s. Some I hadn't even seen for 30, 35 years... They looked pretty good. They're standing the test of time, both in their condition and [in that] I think they look good to me.

DG: What's it like to revisit a painting after so many years? Does it take you back to when you made it, or bring back memories?

DS: Yes, in a way. What surprises me is some of these were over fifty years ago, and people have been born, lived, and died during that time. It just amazes me to see them. When I was painting them here in San Francisco, they were sort of out of character with what was going on in the rest of the art world here. I was almost working with abstraction, and of course, the Bay Area figurative art was what was really hot at the time. Some very good painters like David Park--with whom I studied--and Elmer Bischoff were the best known painters. I was of course younger than them, and sort of painting surreptitiously, under the radar here for a long time. So looking back, I can see how they didn't really fit with the mindset that was going on here. They're landscape based, but they're sort of, as someone mentioned to me, other-worldly: like other worlds, not these. They're almost surreal, in a strange way, but I always thought of them as being influenced by the California landscape that I lived in... They look a little bit out of this world here, now.

Coast Stripe (1961), oil on canvas, 74.5 x 52.5"

DG: Where did you study, and who were some of the influences early on, for you?

DS: Well, probably the first abstract vocabulary I picked up on and learned a lot from was Leonard Edmondson, an instructor at the Pasadena City College. That was actually before I got in the Navy, and I guess it was a little bit afterwards. At 88 my memory is a little bit fuzzy on some of those years. It was based in part on a kind of pictography. Children's art influenced me, and later on Gottlieb's pictograms did, and Paul Klee, Dubuffet, people like that, when I was a student.

My daughter had gone to a wonderful nursery school, the Golden Gate Nursery School, run by a woman named Rhoda Kellogg, who was one of the two experts on children's art in the country. She had a collection of over half a million drawings and paintings that her preschool children had done at this nursery school, and had written books about it, and so I was heavily influenced by her. I don't know how well she's remembered, but she was something else. Learning how children develop their art has stuck with me for all this time, and I'm still intrigued with how they develop basically from abstraction to representation, rather than the other way around, which is what most humans do.

Red Stripe with Blue (1961), oil on canvas, 84.5 x 50"

Untitled (1961), oil on canvas, 96 x 49.5"

DG: When you were coming up as student, who were your peers? Who were the artists that you felt closest to?

DS: Well, I was one of the six people who started the Six Gallery in San Francisco. Wally Hedrick, Jay DeFeo's husband, was the ringleader there. He was the kind of chairman of the board, and the other members were Jack Spicer, who was a professor of English at the art school (it had become the Art Institute by that time), and Hayward King, an African American guy who had a sad ending, but for a while he was the registrar at the San Francisco MoMA, and the director of the Richmond Art Center. Later on, that was.

We were students at this time, in the early '50s... John Ryan, a poet, Deborah Remington, who you may know of, the painter who lived in New York for many years. She died a few years ago, and is having a kind of renaissance there of her work, which is nice, because she was a good painter. Jay DeFeo was a kind of ex officio member. I'm the last one alive of that whole group that started the Six Gallery. Of course, the gallery is famous now for Allen Ginsberg having read Howl there for the first time.

DG: Oh, that's right, yes...

DS: Yeah, it's that gallery. It was one of the first student co-op galleries in San Francisco. There are many of them now, and they come and go, but this lasted about four or five years. They were all my peers, and they're ones whom I worked with and respected. Wally Hedrick I had known since I was fifteen years old. I grew up with him in Pasadena, and he was also one of those who studied with Leonard Edmondson.

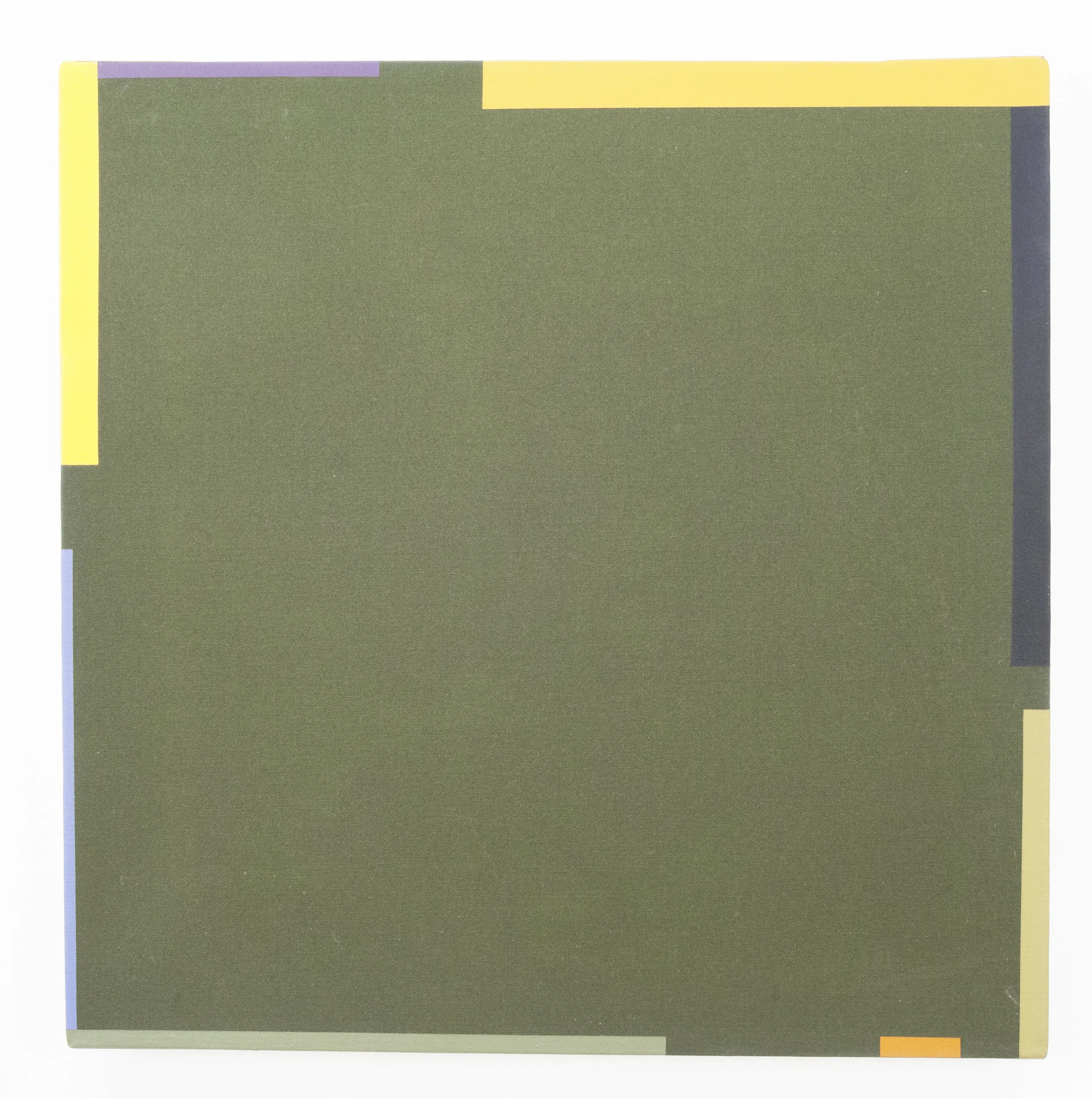

“Pablo” #15, study (1975), acrylic on canvas, 20 x 20"

Untitled (1976), acrylic on canvas, 14.5 x 14.5"

Untitled (1980), acrylic on canvas, 19 x 19"

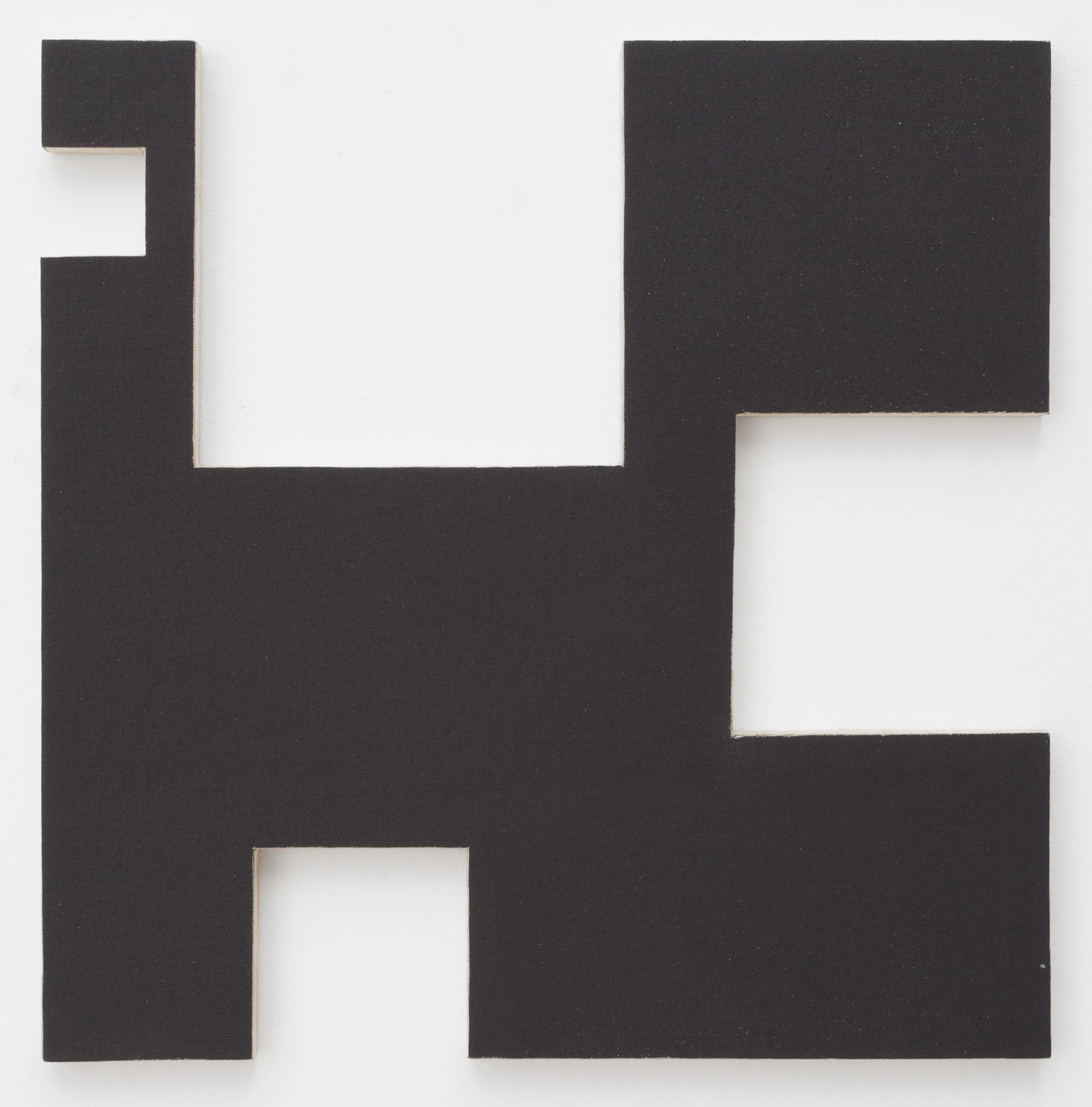

Eccentric Double Plane #8 (Negative Spaces and Positive Places) (1984), acrylic on panel, 16 x 16"

DG: Can you talk a bit about your move from Southern California to Northern California?

DS: Well, I was born in Pasadena, and came up here at Leonard Edmondson's recommendation, to the art school. At first, well, I was on the GI Bill then, and I got a little bit immersed in the North Beach art bars--Vesuvio's and the Black Cat, and all those kind[s] of places. As a student, I couldn't afford to buy many beers, but I participated in that. All of us did, actually, but also... In hindsight, it's the light here. I think it's maybe almost a Mediterranean light. The pure blues here are amazing. The first time the landscape ever really affected me [was] when I went up to Sacramento to teach, my first teaching job in... What was it? 1954, I guess. 1953-54 at American River Junior College. Of course, the landscape is flat there and the skies are amazing. I think the skies still influence me, the skies and water.

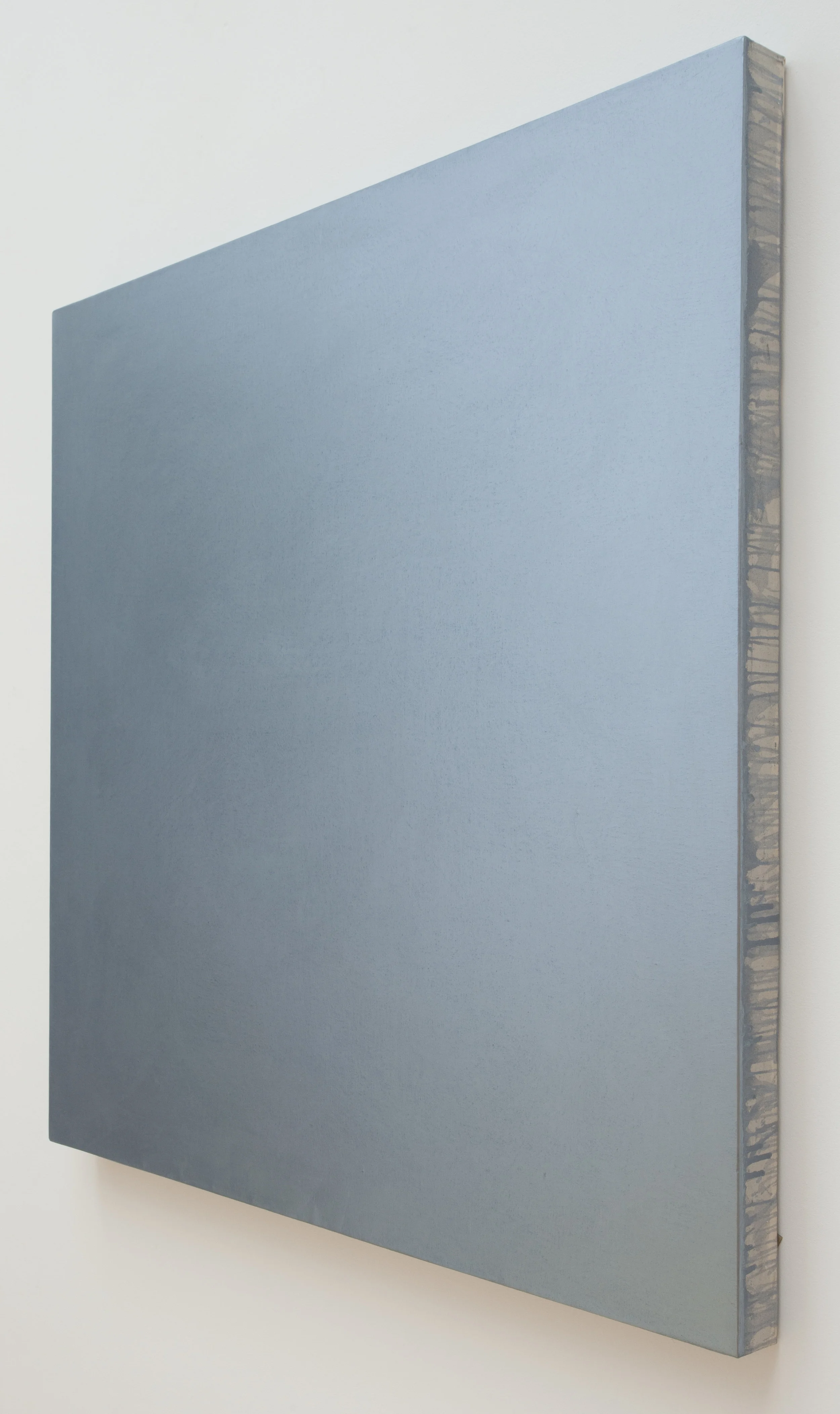

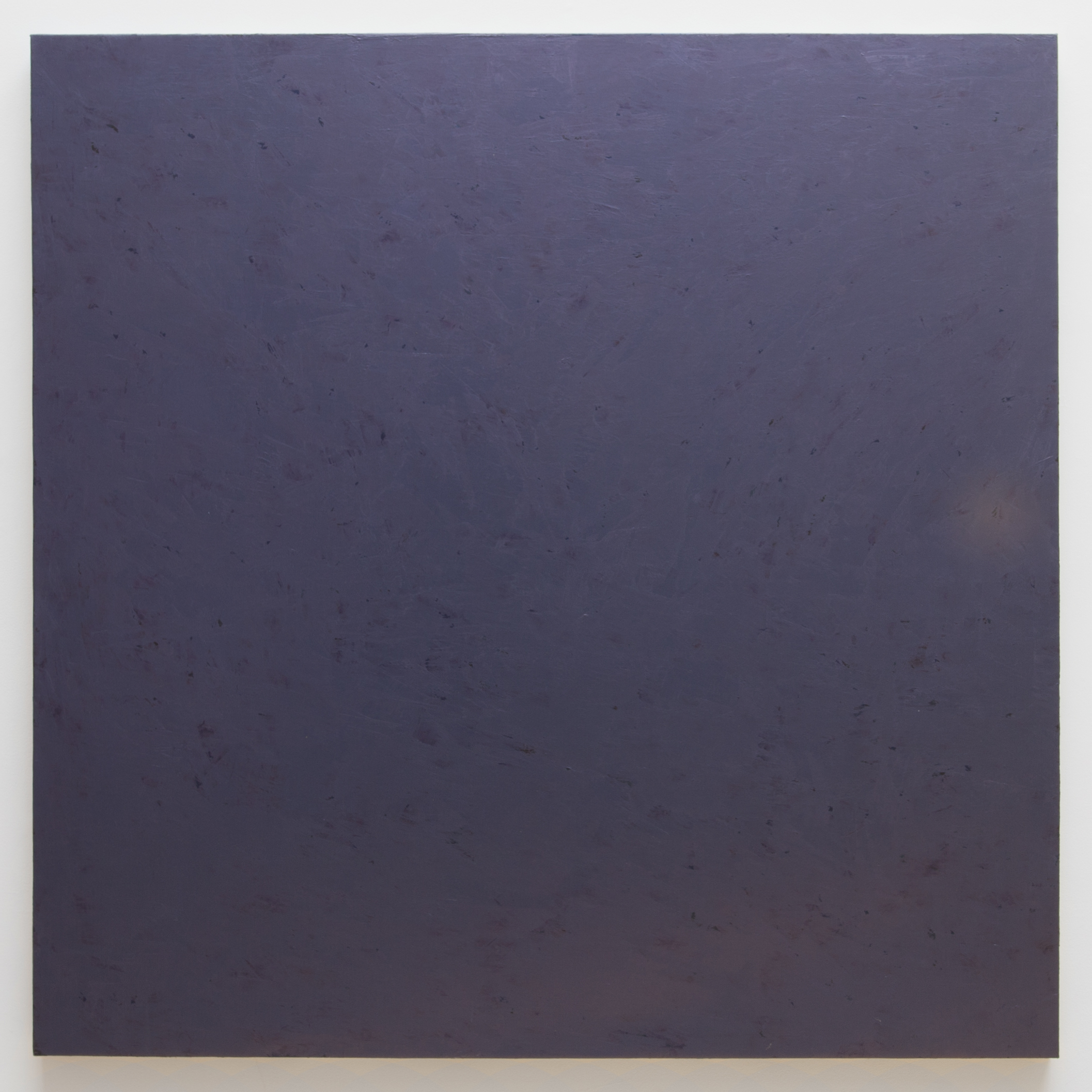

That seems to be a kind of subliminal theme in all of the work that I'm doing even today, skies and water. It's not figurative; it's abstracted, but in essence it's that, and the light. I'm very concerned with light, especially with the pigments I've been using for the last twenty years, the interference pigments which sometimes seem to reflect back more light than they absorb. They're just amazing pigments.

DG: I read somewhere that interference pigments are used by car manufacturers--is that true?

DS: Well, I guess they are used for car finishes. It always amuses me, that because they change color wavelengths depending on your position to them, and their relationship to the sun and so on, how in the hell do the cops, when they're trying to identify the color of a car if it has interference paint, ask a witness, "What color was it?" "Blue. No, it was orange. No..." Because they shift. Usually the shift is complimentary from red to green, purple to yellow, that kind of thing, but very subtle in some cases and more pronounced in others.

I found them in 1998, I think, or '99. They had been on the market for I guess two or three years, the Artist Colors. I don't know exactly, but it was probably after a couple of years. They make six colors, the primaries and the secondaries, and they're off-white. They're very pale, and I just gave it a shot to see what they were like. They also do iridescent metallics, and that's what I started with, but there are ways of mixing them and expanding the palette and making the shifts, and dark and light, and so on. It took me about a year to really figure out how versatile they can be, hit or miss. I guess I could have talked to the manufacturer and found out more. Golden Acrylics is the major source for them, and they do put out a newsletter.

DG: Oh, right.

DS: Yeah, I probably could have learned something from that, but I just went on my own. I felt like an alchemist trying to make gold out of lead, you know?

Metallic Blue Two (1994), acrylic on canvas, 48 x 48"

DG: Ha. Yes. I'm curious then, do your paintings have multiple layers?

DS: I'm not going to tell you my secrets, but they do take maybe 25 coats, 30 coats.

DG: Wow.

DS: I use a combination of brush and a metallic blade spreader, but there's a lot more to it than that... and as I say, it was something that took me a long time to develop. There are all kinds of rigmarole you have to go through to keep the surface flat, and so on. I won't go into that, but I paint a slurry of color on and then I use my spreader to scrape it back off. There's a lot of undercoating going on, and sanding, and other things that I won't go into, because from my experience, when you start talking about process, people's eyes glaze over. They start thinking about sex or something else.

DG: That'll make a good quote! Moving on [laughing]... In some interviews, you talk about creating space with the work. I'm curious if you could talk about that a bit.

DS: Yes. Well, that idea that I wanted to create space goes back to the work from the late '70s and early '80s. Looking back, I can see about five or maybe six major periods with transitions in between. I guess probably I could boil it down to maybe four, three or four, where I discovered a kind of vein of ore that I could mine for several years. One was the landscape-based abstraction, and in the late '70s and '80s it was based partly on the Russian avant-garde, and Mondrian and the De Stijl group, oddly enough. I had become interested in geometric abstraction, but it was also a kind of an attempt to make it lyrical, but what it evolved into was a composition where all of the figures were pushed out to the edge and the center was open.

That was the idea of creating space. What I had done, I realized, [was] turn Rothko inside out. I think he's one of the great 20th Century painters. As you know, he pushed the background out to the edge with the feathery-edged rectangles.

DG: Absolutely.

DS: What I did is push the figure out to the edge. There were bars, rectangular, orthogonal bars and squares and so on, stuck right to the edge. I hit on a surface that also required another 20, 25 coats of paint, and they were done like a watercolor wash, vertically: a six-foot square of 80-inch square painting I put vertically against a floor-to-ceiling easel, and I'd use a big whitewash painting brush to put on a thinned-down coat, watercolor density, from the top to the bottom just like a watercolor wash. Then I'd go around behind the painting and turn it upside down, turn it on its side, so that the paint would run in various directions until it stopped running.

That was kind of a heavy duty physical thing, labor intensive, but it worked. After twenty or thirty coats that way, the surface would become what I describe as like a really dense fog pressed up against a window pane. It was just nice and foggy. Your eye could almost penetrate it. That was a kind of open space that I was trying to create with the different colored rectangles and bars around the edge, and it made your eye sort of like a billiard ball. Your eye would go across the canvas, back and forth, and bounce off these shapes at the edge, but also it opened it up in the center to create the space. This had to do with the planet being overpopulated, you know?

DG: Oh, really?

DS: Yeah, I wanted to create a kind of psychic space, so that your mind could get away from the crowds.

DG: You don't meditate or anything like that, do you?

DS: No, I'd like to try. It would be nice to be able to. I don't do anything like that. I'm not a mystic in any sense, nor do I attempt to go into trances. I don't study Buddhism or anything like that, although I've read about those kinds of things.

DG: But you like this idea of space and thought.

DS: Yeah, this has simply to do with the way sometimes a painting can transport you. I had a saying that I use sometimes, the Vermeer effect. One of the first times I saw a Vermeer in person, it was a very small painting, I think at the National Gallery in Washington. It was only maybe 8 by 10 inches rectangle, and I noticed later that my museum fatigue and everything was suspended, in suspended animation. It just transported me away. The Vermeer just took me into a completely different world, and mind out of body. Sometimes paintings will do that to me. Not often, but those are the ones who I count to be the real masters.

DG: Would you count a Rothko in that as well?

DS: Yeah, Rothko, sure, but in history, Piero does it to me. Oh, some of the American Hudson River School's painters, Fitz Hugh Lane, Albert Ryder, Ralph Blakelock... They just stop me dead in my tracks and put me in another world.

Outerworld View (2015), acrylic on canvas, 72 x 72"

DG: Thinking about recurring elements in your work, color seems to be vitally important.

DS: Somebody asked me how I think of my colors, and there's this story by the anthropologist Desmond Morris, about the painting chimpanzee named Congo. He did a study with Congo, and Congo, his sense of color--they discovered that they couldn't let him choose his own color, because he would mix it all together into mud, just pour, pour everything together.

The experimenters laid out a series of bottles of different colors, and they'd dip a brush and hand it to him with a color. He would use it until he got tired of it, and then he would refuse it, and they would give him another color. That's the way... I'm like Congo. I get tired of it and then move on. I want something else. So it's partly... it's variety, like you don't want to eat the same thing every day. You get an appetite for a different color, or a different shape, or a different approach.

DG: You were born in California, and built your art career there. Did you ever consider going to New York?

DS: No. I've been to New York several times; I don't know how many; I've lost count. Probably, I don't know, 10, 12, 15 times, something like that, but I had never had the desire to live back there. As I said, working out here for a while, especially in the 1950s and '60s, it was pretty much in isolation, but I rather liked that. I didn't want to necessarily be under a microscope.

New York is no longer really the art center of the world. There are art centers all over the world now, and there are terrific painters and artists everywhere, in Europe and in Asia. There also is a lot of foolishness going on too, but that's always been the case.

Alfred Frankenstein, the critic who is no longer alive, and for many years he wrote the art columns for the [San Francisco] Chronicle, he used to point out that in the 1880s there were 25,000 artists living [on] the West Bank in Paris, and how many of them are remembered now?

DG: You've shown a lot in Europe and Italy. What do you think there is about it there, that your work seems to speak to people?

DS: Yes. I think that painters are still held in high esteem in Europe. Here, I'm referred to as "Who's he?" There, I'm referred to as "Hello, Maestro." It's a respected profession, and it's taken that much more seriously than here. They aren't so susceptible to the latest novelty, although it exists there, of course. People are working with computers, and inkjets, and printed sculpture, and all the kind of things that you see often here now, technology in art. That appalls me, really. It's art by a committee.

I can understand why sculptors and muralists and architects obviously need staff, need apprentice help and assistants and so on, but I've always tried to do everything myself that I possibly can, short of weaving my own canvas, and growing my own trees, and milling the lumber for the stretcher bars. I still make my own stretcher bars and mix my own paint, and nobody else touches my painting but me. I prepare the canvas, stretch it, do everything.

My son says: well I'm old school, and I am, because when I look at a painting, I want to know that the person whose name is on it did it, and that's the person I want to admire, not a committee.

I broke my hip six years ago, and I walk around with a cane. I still do all of that, but my son helps me carry things and get materials. This is the closest thing I've ever had to a studio assistant, but he never touches my paintings. He never even watches me paint, but everything else I'm getting help with, which is a blessing.

DG: Do you like the quiet time or the alone time, just being you in the studio?

DS: I rather like that. I listen to music. I love baroque music and dramatic and impressionist composers, and I watch baseball, which is kind of mesmerizing, in a way, and it's one way of keeping in touch with the outside world. But it's soothing things, mostly music I listen to, and I get lost in the work as in a museum with the Vermeer. In fact, all of the aches and pains and other things that bother you disappear.

At the end of the day, I look at what I've done and I sometimes think, "Oh god, how wonderful that you've done that." I bring myself almost to tears. Then I go into the studio in the morning and look at the same painting, and I say, "What the hell were you thinking?"

I've told that story too many times. I'll have to stop it.

DG: I'm curious to hear more about your drawings.

DS: I have thousands of... I don't know; I've never counted them, but thousands of works on paper that have never been seen. It's a way of getting ideas out there, and they're fun to do. They tend to be more surreal. [For] the paintings on paper, I also use the interference paints, but various different colors. I won't go into the techniques, but they're unpredictable. They do often appear to be landscapes... but the way I work, they're unpredictable. I don't know what's going to happen until something does, and it's always a wonderful kind of surprise. The wonderful thing about it is they look intentional, but they aren't.

DG: You used to paint in oil. When did you start painting in acrylic?

DS: Yeah, in the 1960s I stopped painting in oils. That was a mistake in some ways. I was having paintings for the first time shipped around the world, and the oil paintings were damaged too often, so I thought maybe acrylic because it's more flexible, and maybe more easily repaired. I switched to acrylics, and it took me a couple of years to figure out the fact that they aren't at all like oils. I had to re-learn how to paint all over again.

When the acrylics first came out on the market, the manufacturers made them to be as close to oils--in tubes, in that buttery consistency--as possible, so people could make a transition. But that was very misleading. It took me six months to realize that they weren't oils and you couldn't do the same things with them, but I'm glad I did switch because it led to the interference.

DG: Going back to your retrospective exhibition at Haines Gallery... any thoughts come to mind looking over the progression of your work?

DS: I think with me, one thing leads to another. In a sense, I guess people might call it intuition, but one thing suggests another, and I just follow where my paintings take me. That's why sometimes I'm led a little bit astray and get into areas which I struggle to get out of, but the struggle is always an evolution. I've always thought that if you took a photograph of every painting that I did and [made] an animation movie out of it, something like the old Norman McLaren abstract animated films, if you've ever seen those, one thing would morph into another in a kind of logical way, because one painting suggests another.

David Simpson and Cheryl Haines at the opening reception of Now & Then, Haines Gallery, San Francisco, California, September 8, 2016. Photograph © 2016 Nina Dietzel

DG: You've shown with Haines Gallery for a long time... Can you share any thoughts on Cheryl Haines?

DS: Well, she's a terrific lady. She's out to save the world, as you know, probably. She's had internationally acclaimed shows here on Alcatraz, and by Ai Weiwei, the Chinese dissident artist, and others. Yeah, I've been showing with her for over twenty years. She mentioned to me the other day, a week or two ago (we were doing the run of my show there), that it was twenty years.

DG: You have another exhibition up right now. Is that correct?

DS: Charlotte Jackson, my gallery in Santa Fe, has a show concurrently with Cheryl's, and Cheryl's is called Now and Then, and Charlotte's is called Then and Now. They both covered the same span of years. Cheryl's space is larger, so she had more paintings and filled more gaps than Charlotte was able to, but I've been with Charlotte Jackson for probably ten or twelve years.

I'm blessed with some really good galleries: also Martin Muller, Modernism in San Francisco. I'm in the unusual position of having two galleries in San Francisco. Martin Muller specializes in my work from the '80s, the geometric abstractions, because his interest is mainly in that area and in the Russian avant-garde. He was one of the first people to show Russian avant-garde painting here in San Francisco, after Gorbachev. It loosened things up. I think there was one other gallery in New York showing at the same time, but he pioneered that work here, Martin did. Cheryl is one of many that I'm indebted to, and she's terrific. I think she did a beautiful job with the show, with the space she had. It amazed me that she was able to do as much as she did.

DG: Well, I appreciate your taking so much time. This has been great. Thank you so much.

DS: Well, it's been my pleasure, too. To have someone interested in what I'm doing to this extent is always good, always rewarding, and I appreciate it.

DG: Absolutely. Keep up doing the great work. You're an inspiration for a lot of people.

DS: Well, that's good to know if true, so thank you.

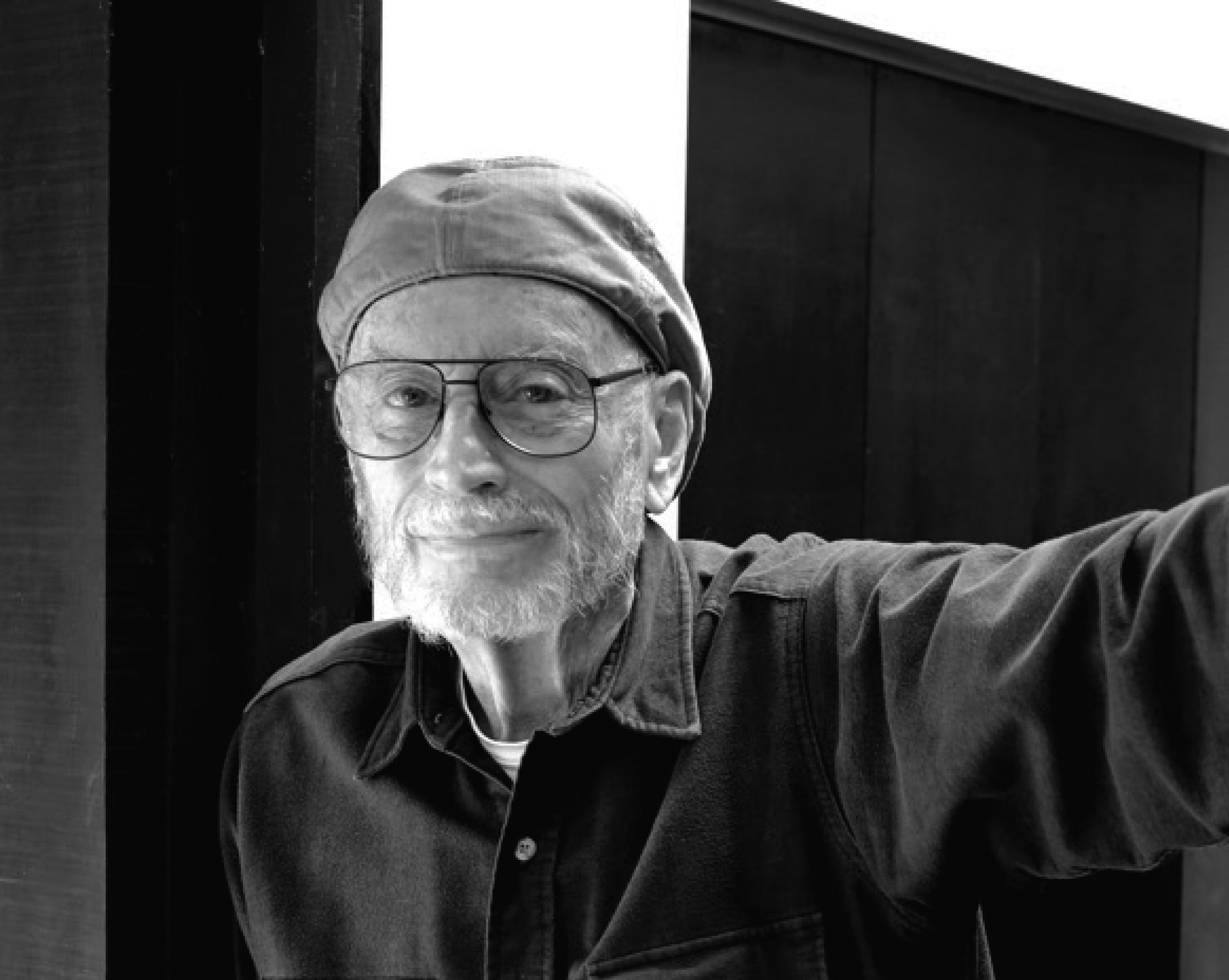

David Simpson in his studio, Berkeley, California, 2015. From David Simpson: Works (1965- 2015) Photograph © 2015 Jo Whaley www.radiusbooks.org

Now & Then: The Work of David Simpson

Haines Gallery

September 8 - October 22, 2016

Featured Image: David Simpson in his studio, 2015. From David Simpson: Works (1965-2015) . Photograph © 2015 Donald Dietz www.radiusbooks.org