TIFF MASSEY

Interview by J. Fiona Ragheb

Tiff Massey is an interdisciplinary artist from Detroit, Michigan. She holds an MFA in metal-smithing from Cranbrook Academy of Art. Her work, inspired by African standards of economic vitality, includes both large-scale and wearable sculptures. Massey counts the iconic material culture of 1980s hip-hop as a major influence in her jewelry. She uses contemporary observances of class and race through the lens of an African diaspora, combined with inspiration drawn from her experience in Detroit.

Massey is a 2015 Kresge Arts in Detroit Fellowship awardee, as well as a John S. and James L. Knight Foundation Knight Arts Challenge winner and a Michigan Chronicle 40 Under 40 award recipient. She has participated in several international residencies including Ideas City (in Detroit, Athens, Greece and Arles, France) hosted by The New Museum of New York, and with the Volterra-Detroit Foundation in Volterra, Italy. Tiff Massey’s work has been widely exhibited in both national and international museums and gallerie

J. Fiona Ragheb: You're a metal-smith, who obviously makes jewelry, and installations, but also wallpaper and more recently, music. What is the connective tissue that runs through the work, or perhaps there isn't?

Tiff Massey: I think in terms of jewelry; I'm just not satisfied with the scale. Sometimes the work can exist just as wearable object. Sometimes it needs to be at sculpture scale: then even larger than that, especially when you're thinking about the landscape. Me not being satisfied is the driving force that promotes synergy and overlap over the various mediums and genres I work with. That’s what I would say about it. As far as the music being incorporated into the work, it’s everything. When I won the Kresge Arts in Detroit Fellowship in 2015, they highlight[ed] each artist by commissioning an introductory video about them. I didn't want to do a generic, "Hi, my name is Tiff. I'm a metal-smith." Yeah, that's boring shit. Everybody does that. I was making music, collaborating with Waajeed. I'm like, "Let's just use this opportunity to make a music video.”

Tiff Massey, Facet, 18.5’ x 4.5’ x 5” (variable), steel, 2010. Image Courtesy of the artist.

JFR: I love that video.

TM: Thank you. It's Kresge's video. That's been an interesting process too, because it's something I created, and there's certain aspects of the footage that I wanted to just isolate away from me talking. But I will never get access to the footage. But if it wasn't for the opportunity I probably wouldn't have made a music video at that time.

It's hard to say within that, but me taking that opportunity to create in this way started to make things more clear. I felt like if I'm using hip-hop basically as a reference for the scale, for the weight, using these references from African culture, and just the idea of bling and it being basically a contemporary version of how African royalty would adorn themselves. I talk about these different symbolisms and everything that goes along with that. I should make more music videos. The goal is to create a visual album, so making more music. I'm working on a second song. My first song interestingly enough was licensed in London and put on a compilation album. NPR named it one of their favorite dance tracks. That’s crazy.

Tiff Massey, 'Detroit is Black' (Rainy City Music)

JFR: Yeah, that's totally crazy.

TM: It's my only song. I'm like, "There must be something within this. Either what I'm saying, or the delivery, or the beat, whatever it is, people are responding to it and I need to do more." I think the visuals really need to speak to what I'm talking about. Usually music videos aren't pairing the visual with the narratives; it's more about budgets, or doing something cool.

JFR: It's really interesting, because I saw the Kresge video, and then I came across the NPR thing, and I made a point of listening to it because I wanted to hear it without the visuals to see what that's like. Of course, it's the whole track, which is not in the Kresge video; that’s definitely something to pursue.

TM: That's actually what I planned on doing, and then I got derailed after coming back from my last trip. I plan on revisiting a body of work that I was working on in 2012, entitled Je Ne Sais Coiff, for my next music video.

JFR: Sometimes your work is shown under the umbrella of craft. Are you comfortable with that characterization? How do you position yourself?

Tiff Massey, Installation view: They Wanna Sing My Song But They Don't Wanna Live It, 2011. Image Courtesy of the artist.

Tiff Massey, Installation view: They Wanna Sing My Song But They Don't Wanna Live It, 2011. Image Courtesy of the artist.

TM: I don't like any of that shit because I don't feel like I fit in really, in any of those categories. Sure, there's craft-based aspects to the techniques that I use, but if that's what you're focusing on I think that's limited as fuck.

JFR: But you don't reject it?

TM: It's not like I'm creating the labels. Yesterday I was in the paper and I have a new title: developer. I'm not creating the titles. It's not like I can combat them. I feel like I'm interdisciplinary. There's definitely a trinity of materials I work with and that's fiber, wood, and metal—and plastic. Other than that, I would never say that I was a craftswoman or person. If it is labeled like that, it's the industry not really understanding the role of an artist outside of being a painter, because painters are huge right now. Muralists, all of this.

Then once it comes to a sculptor or somebody who is doing art that's unrelated to something that is illustration based, I think they are having a hard time understanding or grasping what it is. I told someone that I'm making jewelry and this is what I show them; they would be like, "What the fuck are you talking about?" That's just society and the culture. If we were in Europe, yeah. They would get it. It's just exposure and society that basically deemed jewelry to be in various materials, but it really doesn't count unless it's silver or gold and has diamonds or things like that. That's more because industry controls that.

JFR: You mentioned something about scale, in terms of your shift to installation, because you weren't satisfied. Scale is a really interesting issue because in the art world, there's so much crazy big work that in some cases it's almost a default. In your work, it makes such a fundamental transformational shift. Because you're talking about a shift from something that's of a personal and intimate scale to a scale that is almost autonomous, living there out in the world without benefit of that intimacy.

Tiff Massey, Coils (red), various sizes, powder-coated brass, 2014. Image Courtesy of the artist.

TM: Well, actually I want people to still experience them and have that intimacy, but in another way. This bracelet is basically the prototype for a piece at the Charles H. Wright [Museum of African American History]. I want people to activate this sculpture. I want performances to happen in the interior space. I want people to walk, or do yoga, or run around, around, kids [to] get worn out so they can go to bed early. I want all of that to happen. More so, this scale jump is so people don't have to rush to the gallery to go and see the exhibition. It's something for everyone. Even if you're not a part of this art thing, you can at least have a taste or experience something on your own without somebody dictating what it actually is supposed to mean for you.

JFR: You've said there's always an emphasis on adornment in your work. For me, adornment suggests a very 'performative' experience. What is the role of performance in your work?

TM: Well, just going back to the Kresge video, I think that was more of me getting to that 'performative' aspect. I'm going back to a body of work that I was doing in 2012 called Je Ne Sais Coiff, which is about traditional African hairstyles and how they were symbols of royalty. It just makes sense that I make them jewelry pieces, necklaces. I'm not satisfied with them just being objects, though. I think they need to be performed. They need to be on bodies. I always take images of the work on bodies, so it only makes sense that they stay on them. People need to see how they actually function.

Tiff Massey, Sasha, 22” x 15” x 7”, rope and wool, Molly, 18” x 16” x 5”, rope and wool, Abby, 18” x 16” x 10”, rope and wool, from the “Je Ne Sais Coiff” series, 2013. Image Courtesy of the artist.

JFR: Your work seems very rooted in Detroit.

TM: Definitely. My most recent series have definitely been dedicated to Detroit. It's me being nostalgic about a time [that] really the people who are nostalgic about Detroit aren't thinking about. That's me growing up in the '80s. Detroit was very, very black. Not diverse at all, really. I would have to say that it was a beautiful and positive thing. I use black, the color, as a literal representation of the people and culture, as well as signifiers from childhood that are rooted in African American hairstyles.

Detroit, there's a lot of politics behind her. A lot of people are about the newness of Detroit, and I think it's positive, but it's hard to think that there's positivity within the new when no one is thinking about the preexisting infrastructure, and the people that have lived here prior to these new narratives. It's very, very frustrating to witness and to be a part of because it's happening so quickly. No one--I don't think--five years ago probably would have ever expected this to happen. I like to create juxtapositions within my work with the newness and a time of Detroit I was very, very nostalgic about.

Tiff Massey, You Good, 13.5″ x 18″ x 1.5”, acrylic on wood, 2016. Image Courtesy of the artist.

Tiff Massey, What Up Doe, 13.5″ x 18″ x 1.5”, acrylic on wood, 2016. Image Courtesy of the artist.

JFR: It sounds as if you feel you have a responsibility as an artist working in Detroit.

TM: Yes and no. It's kind of hard, because usually I get the platform to speak or to talk about things, or I'm invited to biennials internationally where Detroit is the subject matter. No one is actually talking about the things that I'm talking about. So then it becomes a responsibility for not only the narrative to be heard, but then it's not just about me and what I'm nostalgic about or what I want to visually represent. It's really me speaking for a group of people who don't have the opportunity to be heard, I guess you could say. It becomes more political because people often say, "Oh, it’s so great, everything that's going on." What are you basing that on? Because we have tons of places that serve small plates and artisanal cocktails?

We have schools that are defunct, transportation that barely works. A lot of money just went into creating this Mr. Rogers Trolley. They call it the Q-Line; it doesn't go anywhere. It's really some ego shit that's happening, more so than anything. So I don't know. The change is definitely not for the people of Detroit. It's for the tourists… that's what they're trying to capitalize on, tourism.

JFR: The fact that you just bought a building is fantastic. As a Detroiter, don't you want your own piece of the city before everyone else gets it?

TM: Exactly. I had to shift my focus, too, in a way I didn't necessarily feel like I wanted to at the time, but I had to, especially when I think about longevity... well, just longevity in the city. If I didn't go and step out to try to acquire some property… no telling when I would be able to do it. Because right now, as far as I know, it's hard for artists to find space. That's more of what I'm talking about. You can get anybody to have an idea about developing these areas but that was never the focus. The focus is to bring the people in, to change the narrative of Detroit, to change the look of Detroit to attract all these other people that aren't Detroiters. That's what it is; that is what's happened. That is what we're looking at.

JFR: You talk about going to biennials where Detroit is represented and whatnot; so there is a lot of privilege and opportunity that comes with that. At the same time, you've also said you don't necessarily want to carry the mantle for being a Detroit artist, or the Detroit artist.

TM: Yeah, that's definitely true because I think there's more to me than the land on which I grew up. I definitely talk about other subject matter besides Detroit. Usually, appropriation of black culture. I don't really see a difference in gentrification and co-opting Detroit by all of these suburban businesses. I really don't necessarily see a difference between those two ideas; so I guess that's what the overarching theme is. The observation of the culture vulture.

Tiff Massey, Detail: Noir Quilt Code 2, 180” x 72” (variable), wood, 2015. Image Courtesy of the artist.

Tiff Massey, Installation view: Noir Quilt Code 2, 180” x 72” (variable), wood, 2015. Image Courtesy of the artist.

JFR: Well, that brings up a really interesting issue. Because you've been a little bit critical about industry and corporations jumping on a Detroit bandwagon, but at the same time you're in a new Adidas campaign.

TM: A global campaign with Adidas, yes.

JFR: Is that a necessary evil?

TM: Well, actually I get what you're saying. It's hard for me to think about that in relation to what they're doing, because they didn't just go to Detroit. They went to Chicago, too. They're going to all of these other cities to highlight artists: musicians specifically. I think out of the entire campaign that they're doing, and all these other cities, I'm the only visual artist. I don't think that's the same as people coming to Detroit for two days and writing about the train station, or others that want to come and want to buy a house, and do that same shitty-ass project and then leave. Adidas just recently put on a free concert in Detroit with those musicians that were a part of the campaign for Detroit. This is the give back. Yes, we've come to your city. We've highlighted some artists that we think are amazing. Here, we want to share this with you.

Usually, when I'm talking about Detroit, I want you to get a vibe of what it is. It's not only about the wearable sculptures that I make. For instance, the wallpaper and mirror installation I created for the Saint-Etienne Design Biennial this year... Usually, I have jewelry that accompanies the wallpaper, which is made from Detroit images, from the earliest I can find, juxtaposed with photos of weeds that I took on Belle Isle. All these things are elements of what I experience on a regular basis. There isn’t just one type of experience at a time. The mirrors have a chain link fence motif. It's mirrored as reflective so you are a part of it: but which side are you actually on?

Tiff Massey, Detail: 1960s: Detroit Flore et Faune, 1920-1960s, from the ‘B(l)ack Then They Didn't Want Me Now I'm Hot They All On Me’ series, dimensions variable, wallpaper, 2017. Image Courtesy of the artist.

Tiff Massey, Detroit Flore et Faune, 1920-1960s, from the ‘B(l)ack Then They Didn't Want Me Now I'm Hot They All On Me’ series, dimensions variable, wallpaper, 2017. Installation view at the Biennale Internationale Design Saint-Etienne 2017 in Saint-Etienne, France. Image Courtesy of the artist.

JFR: It's interesting, because adornment could be perceived as highly gendered, but in your work it's very powerful and unapologetic, as opposed to feminized. I'm guessing that's because of its relationship… it’s almost ceremonial in a way. Is that because you're looking to hip-hop and African culture?

TM: I would definitely agree with that. Even when I started dabbling in metals in high school, I was really obsessed with those lucite rings. I wanted to replicate lucite rings in metal. Then it became a weight issue. Then I learned to fabricate the illusion of the weight. That's basically where it started. The lucite rings, I just remember loving them as a kid.

Yes, it's very interesting when people hear that I make jewelry that they think is women-specific. I think my work is gender-neutral and it is about you making a statement. I think the same pieces that are placed on a woman would look equally as good as [on a] man; it's just society has shifted the way that men look at adornment. Because they were wearing pearls, all kinds of shit, back in the day.

JFR: They were even wearing pink. Baby boys used to wear pink and baby girls wore blue. Pink was perceived as a stronger color, so baby boys wore the pink and girls wore blue because it seemed softer. So it is interesting the ways things change. I wanted to go back to the point you just made about the use of metals. You wanted to fabricate the weight, I think is the way you characterized it, because so much of your work could be fabricated in something else. One thinks of fibers, but it is metal. Obviously, you're trained as a metal-smith but there's more to it than that.

TM: Yeah. It just basically goes to my point; I want people to feel me. You are going to be very aware of the piece that you are wearing if it has weight to it. If it's something that's light, you're just going around your every day business because it's like it's not there. I don't like little trinkets. I don't like jewelry that you can't see, because I feel like: what is the point? That's the reason why this scale is the way that it is, and most definitely because I'm referencing hip-hop--it is a ceremonial thing. I've made it. I got this contract. I am a part of this organization.

Usually when artists are signed to that particular organization, aka label, they all have the same chains and wear them collectively. It’s more of a tribal belonging aspect. I think that’s next for me--to investigate with the use of technology the idea of belonging.

Tiff Massey, Power, from the series ‘They Wanna Sing My Song But They Don't Wanna Live It,’ 48″ x 16’’ x 8”, powder-coated steel and wool, 2011. Image courtesy of the artist.

Tiff Massey, Coolio, from the series ‘They Wanna Sing My Song But They Don't Wanna Live It,’ 16” x 8” x 6”, plastic, hemp, wood and gold leaf, 2011. Image courtesy of the artist.

JFR: I wanted to parse what you said a little bit further, when you said, "I want them to feel me," in terms of wearing the pieces. Do you mean in the sense of feel what it's like to be me, walk in my shoes, or do you mean to feel themselves, or…?

TM: To me, it's hard to separate me from the things that I make. In that regard, it's just the physicality of what I made. What happens when the wearer is adorned? They feel themselves and they want to look at themselves. They walk differently. It’s really interesting. This year for FashBash [a fashion oriented museum fundraiser] my friend was like, "Oh, I need a Tiff Massey. I need a Tiff Massey." I lent him one, just to watch him. He was like a peacock. His girl was even mad that he didn't get a Tiff Massey for her. He was only thinking about himself. He was like, "Yeah, I was all up in the papers. Everybody asked, who made my necklace?" He was really feeling it. He's a confident man, but this was to the next level. That's what I like to see.

JFR: That also goes back to the notion of performance. It doesn't have to be a literal performance in terms of the music video, but in terms of the way we perform ourselves. For oneself, but also for the rest of the world. It's interesting how that shift happens when you put on one of your pieces.

TM: I have some images, too, from an exhibition in 2014 at the Simone DeSousa Gallery. My photographer captured some of the people investigating because you could pick up the jewelry and try it on.

JFR: The Four Mirrors from the series 'B(l)ack Then They Didn't Want Me Now I'm Hot They All On Me': I've seen that as just four mirrors, but I've also seen it as four mirrors with some of your wearable pieces. Is that the same work, different iterations of it?

TM: It's the same work, different iterations. The work was originally exhibited at Craft in America in Los Angeles. They are partners, so each mirror has a necklace. That's initially how I wanted the work to be presented.

Tiff Massey, Four Mirrors, from the ‘B(l)ack Then They Didn't Want Me Now I'm Hot They All On Me’ series, 2016. Image Courtesy of the artist.

Tiff Massey, Detail: Mirror 1, from the ‘B(l)ack Then They Didn't Want Me Now I'm Hot They All On Me’ series, 17 7/8″ x 13 3/8″ x 1 3/4″, wood and fiber, 2016. Image Courtesy of the artist.

JFR: Even the choice of your word partners suggests two roles being performed, in a way, as opposed to two parts.

TM: I wasn't thinking about them being separated from each other. When it was exhibited at Rush Arts Gallery in New York in April and May, they separated all the mirrors and the wearables. I would have never made [that] choice, because of how I envisioned the work. That's where that came from. To me, it was nice to see as well, because a lot of people spent a lot of time in front of the mirrors. It's that voyeuristic aspect that I like to capitalize on. Usually, when I'm talking about these political subject matters a lot of people say, "I don't have anything to do with this. This is not me." Whatever. It's like, "No, your ass is in it." Literally. It's you. At least it's you for right now, in this moment.

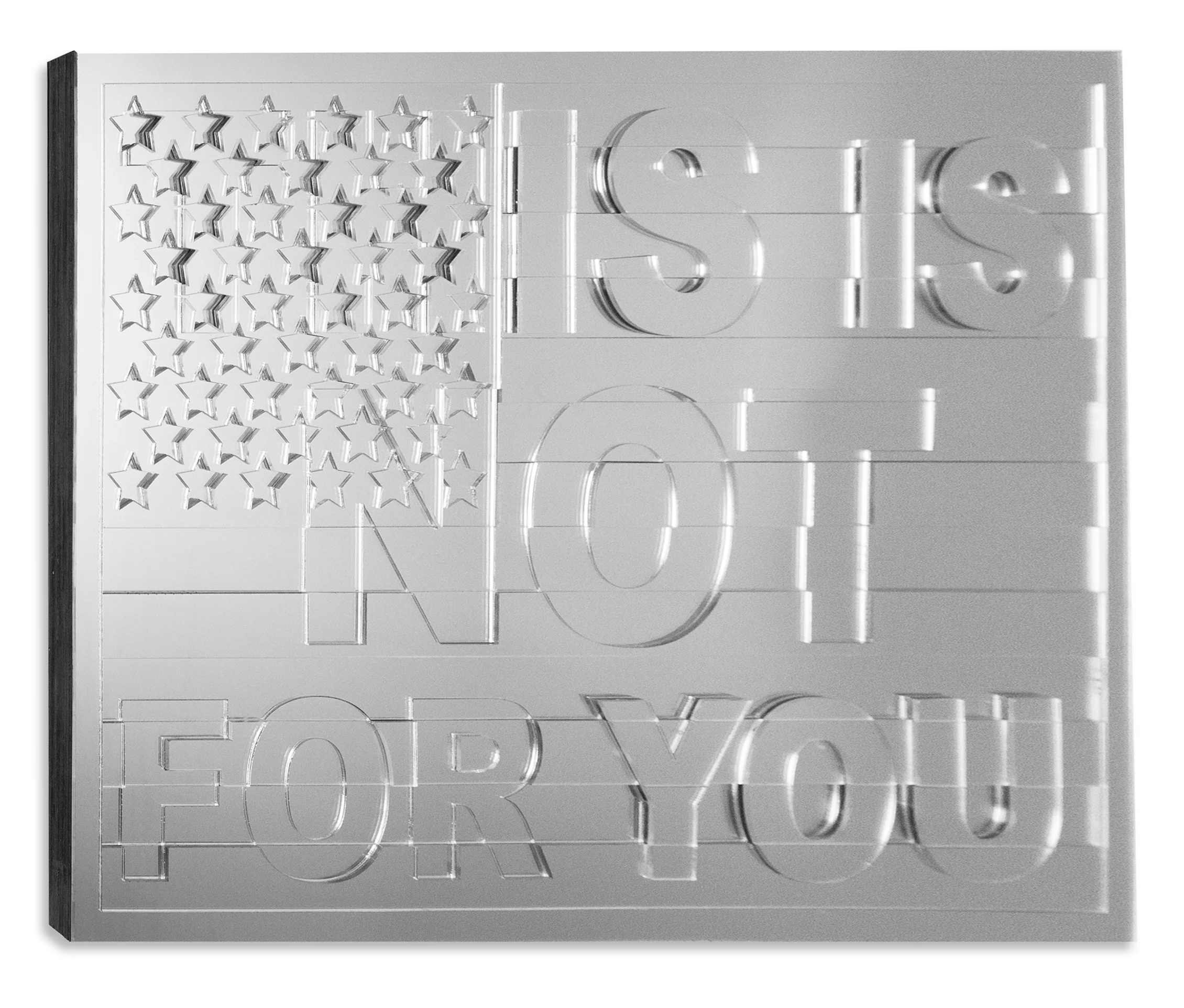

JFR: To me, it's two very different works, with or without the pieces that you try on. Speaking of being in it and not escaping it, this piece which says “this is not for you,” seems literally in your face. You can't escape that. You literally can't escape it. It's in your face and you're in its face because of the mirrored surface, if you will. We talked about the relationship, the context for Detroit. What about the broader context, in terms of your place in the world, in the trajectory of contemporary art? You look at a piece like that and you think of all kinds of artists: Glenn Ligon, Jasper Johns... is that something that you think about?

Tiff Massey, Ain’t No Future in Your Front, 26″ x 38″ x 1.25″, wood and mirrored acrylic, 2017. Image courtesy of the artist.

TM: Totally. Glenn Ligon's flag to me is genius. When I was initially thinking about the flag, of course we're dealing with Trump era. A lot of people have these ideas of what America should be, could be, was. I have the words within the flag that says, "This is not for you." The words that actually come out further into space say, "This is you." You've created this. This is actually what you're projecting and yes, you helped create this, regardless [of] if you think you did or not. Definitely heavy on the politics. Initially I was thinking about having two flags that mirrored into each other. One would be the Black Nationalist flag mirrored inside of the American flag. Even though they are very distinct within the positioning, the color is just reflecting into each other and the distortions that they would create; I was interested in that.

JFR: You had mentioned nostalgia earlier. When we were speaking about this piece, you talked about where we are, where we could be, where we were. It's particularly compelling given the politics of nostalgia that inform the current political climate.

TM: It's interesting.

JFR: You're taking what for you are positive aspects of nostalgia, but there are others who would use nostalgia in a completely different way.

TM: Totally. That's more like the political climate that got us here, white supremacy. Like me being nostalgic about Detroit, and there's two narratives... There's the Detroiters that left during the white flight that would say Detroit was so great before the rebellion. As Detroiters that have been here after the rebellion, we're like, "Detroit? Yeah it has issues," but what people would say from the suburbs--that's not the relationship that we had. I think my nostalgic perspective of Detroit is a perspective that nobody else is focusing on. Because when a lot of people think about Detroit: Detroit has been used as the pejorative for so long. I remember even growing up, being in high school, and I would go to Royal Oak. They would have these crazy t-shirts that would have Detroit spelled in the shape of a gun. Now you see the shift. "Oh, yes Detroit. I am Detroit. Detroit this, Detroit green, Detroit water." Sometimes I joke, what are they going to call Detroit? They're already putting "new" in front of it. Do you know what I'm saying?

JFR: No, I don't know what you're saying.

TM: New Detroit. Have you not seen--? Yeah. There is a "new" Detroit. People are using this within their branding, all of these things.

JFR: Everything that's old is new again.

TM: Nah.

Featured Image: Tiff Massey in her studio. Photo by Esther Boston