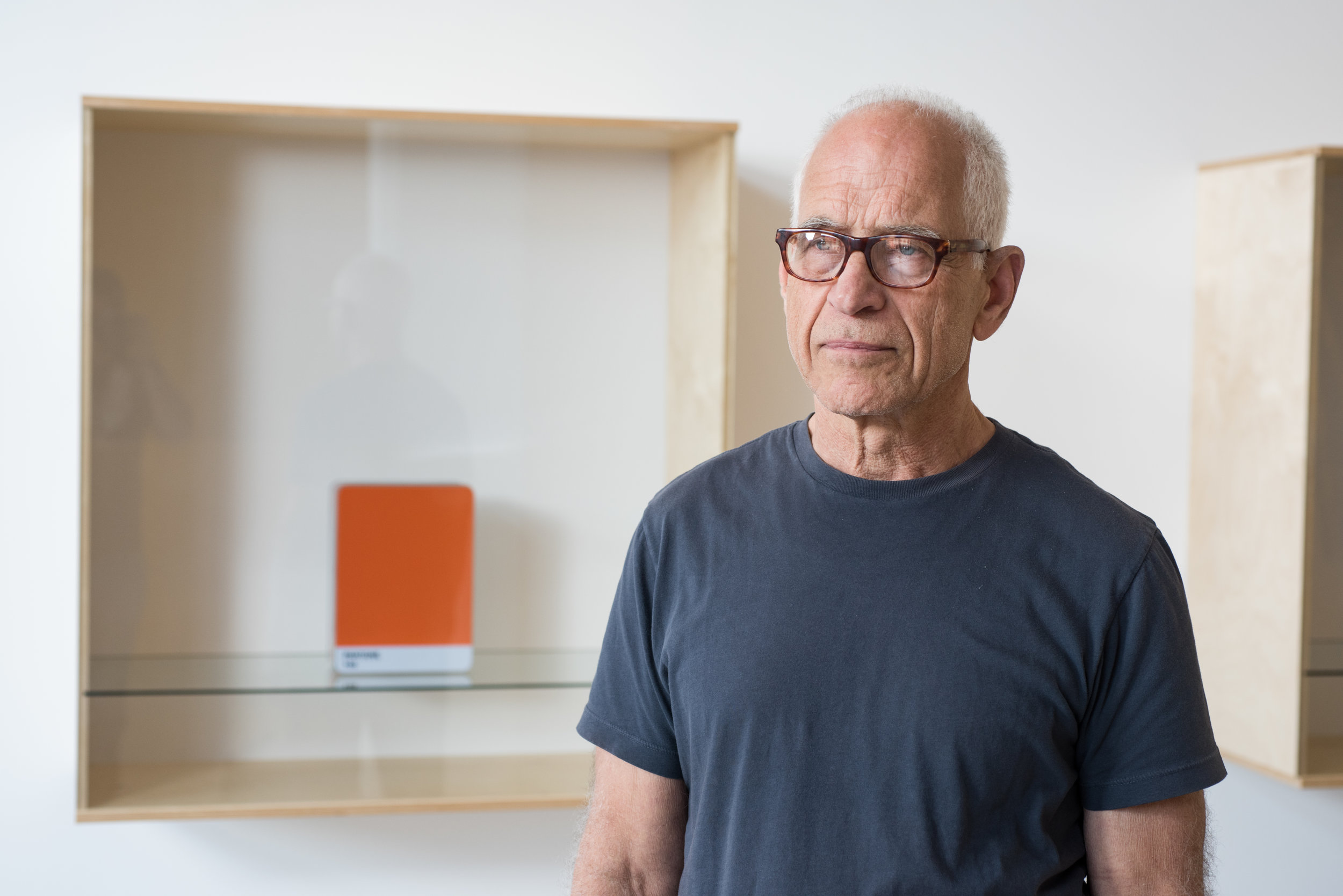

HAIM STEINBACH

“You can visualize things mathematically. For instance by placing two dog chews next to a lunch box in the shape of Darth Vader’s head... What does that say about lunch?”

Interview by Amanda Quinn Olivar, Editor

Born in Rehovot, Israel in 1944, Haim Steinbach has lived in the United States since 1957. He received a BFA from Pratt Institute in 1968, followed by a MFA from Yale University in 1973.

For more than four decades, Steinbach has explored the psychological, aesthetic, cultural and ritualistic aspects of collecting and arranging already existing objects. His work engages the concept of “display” as a form that foregrounds objects, raising consciousness of the play of presentation. He selects and arranges objects—which range from the natural to the ordinary, the artistic to the ethnographic—thereby emphasizing their identities, inherent meanings and associations.

The artist’s work is represented in the permanent collections of The Museum of Modern Art, New York; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; The Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas; The Guggenheim Museum, New York; Tate Modern, London; The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Albright Knox Museum, Buffalo; The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; The Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; The Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; Centre George Pompidou, Paris; The Israel Museum, Jerusalem; Museum Moderner Kunst, Vienna; and The Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago.

Amanda Quinn Olivar (AQO): In the mid-’70s, what led you from painting into your epic journey of collecting, making art with, and displaying found objects?

Haim Steinbach (HS): In the early ‘70s, I was a graduate student at Yale University. I argued for Duchamp’s urinal and coat hanger. He introduced these objects to the museum. And Robert Smithson was bringing rocks from “site” to the museum, a “non-site,” and Joseph Kosuth was showing photocopies of definitions of words from the dictionary, like “idea” or “chair.” I was intrigued by the question of the “object,” specifically the object in art.

AQO: What kinds of things were you looking for, and where did your search take you?

HS: By 1975, I figured out that the everyday object would be key to the investigation of meaning in art. Performance art became part of our consciousness of interpersonal and aesthetic relations. But there was also the question of object to object relations. Forty years later we have a branch in philosophy named “speculative realism” and “object oriented ontology.” We also have the internet and virtual reality.

Display #6B - with Gordon Matta-Clark, 1979/2014, Galvanized steel studs, plasterboard, wallpaper sections, wood shelf, metal brackets, polyester and glitter vest on metal hanger, stuffed cotton lamb, painted stones, ceramic vase, wooden box, stuffed cotton lion, metal desk lamp, conch, wooden salt and pepper shakers, Dimensions variable, Photo: Hugo Glendinning. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles

AQO: Please tell us the ideology behind your practice…

HS: Placing objects. What’s next to what and what happens when something is replaced with something else.

AQO: When curating your own installations, what is most important to you about the visual experiences you create? Are you interested in what your audiences take away?

HS: I am interested in the audience. It’s interesting to watch the responses, especially what artists do with objects today. You can visualize things mathematically. For instance by placing two dog chews next to a lunch box in the shape of Darth Vader’s head... What does that say about lunch?

AQO: Did arranging items on shelves always captivate you? Where do you think your interest in display as art and communication came from?

HS: I was drawn to the question of art and performance. When I was a kid my older cousin took me to the theater in Jerusalem. We saw the play Emil and the Detectives. There was a baseball bat that was a useful weapon. It was just a baseball bat; I was fascinated by it. It has an unusual shape and form. We didn’t have baseball in Israel. I still haven’t made a work with that. I have to make it now.

Shelf with Racoon, 1983, Painted wood shelf, plastic frisbees, stuffed raccoon mounted on wood, 33 x 34 x 11 ¼ in. (83.8 x 86.4 x 28.6 cm), Photo: David Lubarsky. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles

AQO: Is there room for spontaneity or do you plan everything out? Do you make maquettes, storyboards, studies experimenting with different scenarios?

HS: This reminds me of Emil, I see the baseball bat again and it’s taking on a new meaning for me.

AQO: Do you carry a common narrative theme across different series?

HS: Every object already has a narrative. It changes all the time.

Display #105 – pinkraspberry, yellowsubmarine, bluevelvet (installation view), 2019, Galvanized steel stud wall, plasterboard panels, acrylic paint, 120 x 292 x 4 5/8 inches (304.8 x 741.7 x 11.7 cm), Edition of 2. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles

AQO: How much research do you do? Has it ever changed the concept behind a particular work or series?

HS: I research all the time. Usually when I wake up in the morning, I stay in bed for a while thinking.

AQO: Did your upbringing influence your artistic views and path? Is your story represented in your work?

HS: We have been sitting around the table for the Passover meal every year and reading the story of the Haggadah. I like the Haggadah… It’s full of allegories. I have been inspired by it.

closed at sunset except for fishing, 2019, Plastic laminated wood shelf, CB radio antenna, plastic Latin Percussion "Super G¸iroî, plastic G¸iro scrapers, ceramic donkey head, 43 5/8 x 71 x 21 inches (110.8 x 180.3 x 53.3 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles

the nutcracker, 2018, lastic laminated wood shelf, electronic smart speaker, brass apple, wooden bust, wood peppermill, 48 ¾ x 45 ½ x 12 ½ in. (123.8 x 115.6 x 31.8 cm). Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles

AQO: How did you go about planning and curating your new exhibit Appear To Use at Tanya Bonakdar gallery in Los Angeles? Is there a meaning to the name and theme to the exhibit?

HS: My son River was given a present of a smart speaker a year ago. He plugged it in in the living room. I ignored it for the whole year. One day my partner Gwen said, “Why not use a smart speaker?” It so happened that I have been reading Giorgio Agamben’s book What Is an Apparatus, and instantly the sentence “appear to use” flashed.

AQO: Since my gallery visit, I’ve been thinking a lot about your found text works. When did you start collecting text, sentences and phrases as objects, and where do you find them? Please tell us how you use these objects to manipulate and play with space, scale and dimension.

HS: Writing is architecture, as are words on a page. Since the Industrial Revolution we see words on billboards and in magazines. Words are designed and given a typeface. I pick sentences I like and transfer them in their original typeface to the wall. In 1986, I introduced a text to a wall I designed for the exhibition Damaged Goods at the New Museum in NY. In 2014, this work was on the wall again at the Hammer Museum. It was part of the show Take It Or Leave It. It stated, “now you can afford to stop driving each other crazy.”

mypoemisfinishedandIhaven’tmentionedorangeyet, 2019, found text from the poem “Why I Am Not a Painter” by Frank O’Hara, matte black vinyl, acrylic paint, dimensions variable, Edition of 2. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles

the band if it is white and black the band has a green string, 2019, found text, matte black vinyl, dimensions variable, Edition of 2. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles

AQO: What is the most unconventional material you’ve worked with?

HS: Shit. It was the early 1980s, when the East Village in NY was ripe with new small galleries run by young artists. The word came about a show open to all. It was titled The Shit Show. I put some shit in a glass jar and set it on a shelf. I knew that the Italian artist Piero Manzoni had made a work canning his own shit. Mine however was dog shit. I picked it up on the street. I believe that was around the time when the city passed a law requiring dog owners to dispose of their dog’s shit.

AQO: Your box Untitled (Pantone 17-5641) is almost like a hard-edge abstract painting. Did the idea stem from your painting days? What led you to use Pantone color and found boxes? (and by chance, does Pantone sponsor you?)

HS: Gwen got me some Pantone boxes. They sat on my studio floor for a few years. Then one day the ideas popped up. Yes, they are paintings. I did not ask Pantone for permission to paint.

Untitled (Pantone 17-5641), 2016, Baltic birch plywood, plastic laminate and glass box, metal Pantone storage box, 41 3/8 x 39 3/8 x 17 1/2 in. (105.1 x 100 x 44.5 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles

AQO: Please relate a memory that influenced or changed your outlook and career.

HS: That’s a difficult one. I must search for an early trauma.

AQO: What is your favorite art accident?

HS: I have several. I consider such [an] accident to be an encounter with something you don’t understand. When it becomes part of your life, it’s transformative.

Installation views of appear to use, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, Los Angeles, March 10-May 18, 2019. Photos: Jeff Mclane. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles

Feature portrait by Youval Hai, 2018