OLAFUR ELIASSON

“It’s very encouraging for me to see the way an artist like myself is today invited to the table to have discussions with policymakers... . I think art has something special to offer these fields, since artists deal on a day-to-day level with touching and reaching people emotionally and aesthetically.”

Interview by Amanda Quinn Olivar, Editor

Olafur Eliasson was born in 1967. He grew up in Iceland and Denmark and studied from 1989 to 1995 at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. In 1995, he moved to Berlin and founded Studio Olafur Eliasson, which today comprises numerous craftsmen, architects, archivists, researchers, administrators, cooks, programmers, art historians, and specialized technicians. Since the mid-1990s Eliasson has realized numerous major exhibitions and projects in museums, galleries, and institutions around the world, and has also produced numerous prominent projects in public space.

In 2012 Eliasson and engineer Frederik Ottesen founded the social business Little Sun. This global project provides clean, affordable energy to communities without access to electricity and raises global awareness. Eliasson and architect Sebastian Behmann founded Studio Other Spaces, an international office for art and architecture, in Berlin in 2014. In 2019 the United Nations Development Program appointed Eliasson as a Goodwill Ambassador for climate action and the Sustainable Development Goals.

Eliasson lives and works in Copenhagen and Berlin.

Amanda Quinn Olivar: How did your upbringing in Denmark and Iceland shape your work and influence your path?

Olafur Eliasson: My interest in light and the effects that light has on how we live, work, and think definitely comes from my memories of the particular lighting of the long Icelandic summer evenings and the darkness of the winter. When I was growing up, however, I had a very naïve idea of nature – I thought of Iceland as Nature and Denmark as Culture, and I thought there was a great difference between the two. Today I see this as much more complex, recognizing, for example, that the characteristic Icelandic landscape was radically shaped by humans through deforestation and the sheep that were brought there by settlers a thousand or so years ago. I also cannot deny that a certain Scandinavian worldview affects my work and my approach to making art. I have a strong belief in the value of collaboration and community, of We-ness.

Amanda: Your Glacier Melt Series 1999/2020 is an especially relevant project to talk about right now. Can you tell our readers about the series, and your experience revisiting the glaciers after twenty years? Was there a specific moment or impetus that inspired this series?

Olafur: The thirty pairs of photographs that make up The glacier melt series 1999/2020 were to be shown in my exhibitions In real life in Bilbao and Sometimes the river is the bridge in Tokyo—prior to the COVID pandemic.

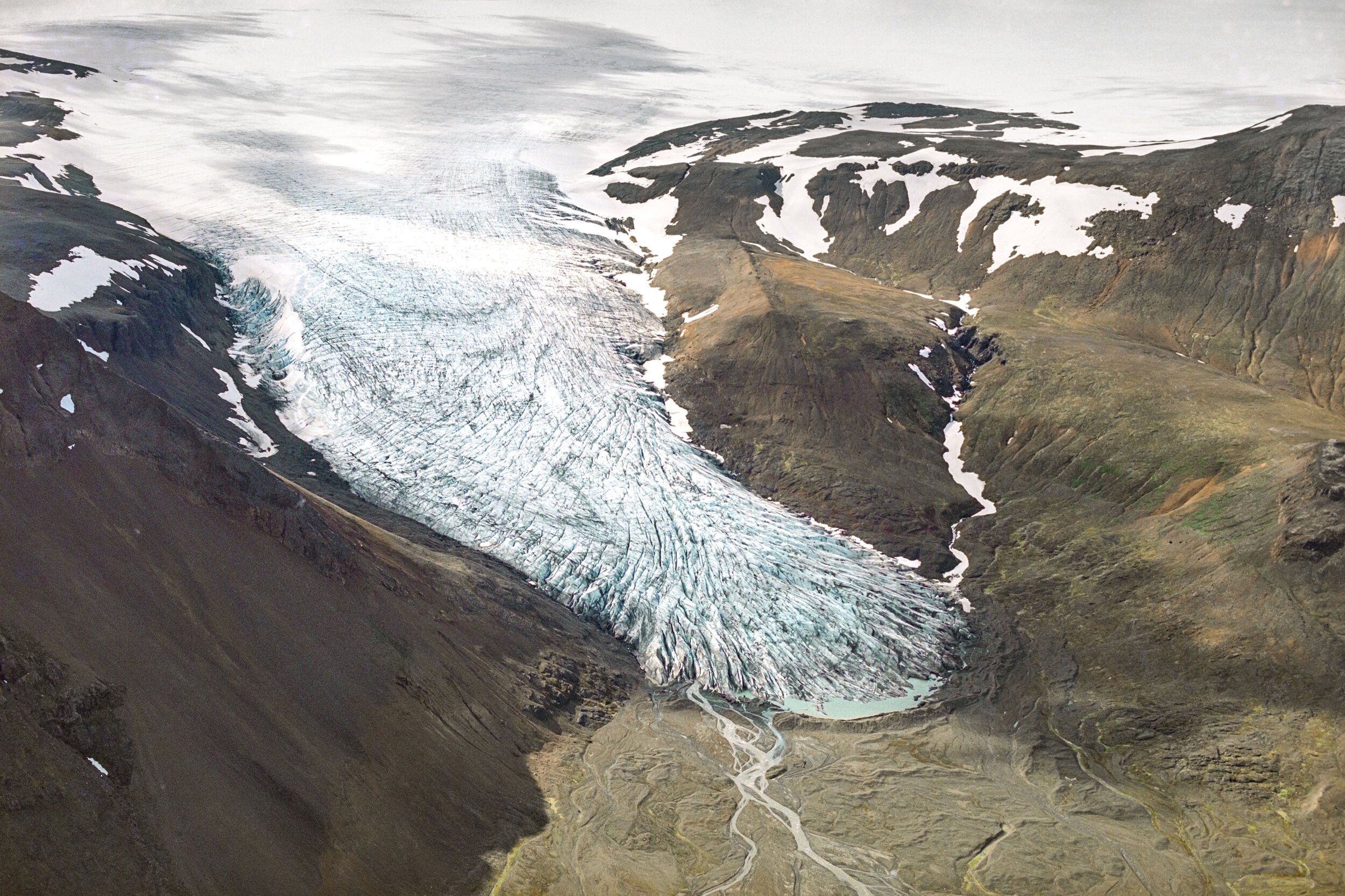

When I first shot the glaciers in 1999, the climate crisis was not directly on my mind. I was photographing a range of natural phenomena and landscapes around Iceland at the time and was focused on finding a way of capturing the sheer scale of the glaciers. The best way to do this seemed to be from an airplane, because all the images I took while standing on the glaciers were somehow disappointing. Now, twenty years later, the climate crisis and the melting of the glaciers are very much on my mind. Ice Watch for example, the large blocks of glacial ice that I brought from a fjord outside Nuuk, Greenland, to public squares in Copenhagen, Paris, and London was very much about raising awareness of climate change on the occasion of international climate summits.

So looking back at this series of photographs from 1999, it seemed obvious to go back and check in on the glaciers. Of course, I expected them to have changed somewhat, but I was truly shocked to see how much they had melted. Some were even difficult to locate again, they had changed so much. Around the same time that I was re-taking the photographs, I took part in a ceremony to mark the passing of Okjökull, the first of Iceland’s glaciers to be declared officially gone as a result of climate change. I hope that the attention that this has received will motivate people to act and put more pressure on governments around the world.

Olafur Eliasson

The glacier melt series 1999/2019, 2019, detail (Fláajökull)

30 C-prints, each 31 x 91 x 2.4 cm

Courtesy of the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles © 2019 Olafur Eliasson

Olafur Eliasson

The glacier melt series 1999/2019, 2019, detail (Fláajökull)

30 C-prints, each 31 x 91 x 2.4 cm

Courtesy of the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles © 2019 Olafur Eliasson

Olafur Eliasson

The glacier melt series 1999/2019, 2019, detail (Krossárjökull)

30 C-prints, each 31 x 91 x 2.4 cm

Courtesy of the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles © 2019 Olafur Eliasson

Olafur Eliasson

The glacier melt series 1999/2019, 2019, detail (Krossárjökull)

30 C-prints, each 31 x 91 x 2.4 cm

Courtesy of the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles © 2019 Olafur Eliasson

Olafur Eliasson

The glacier melt series 1999/2019, 2019, detail (Rótarjökull)

30 C-prints, each 31 x 91 x 2.4 cm

Courtesy of the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles © 2019 Olafur Eliasson

Olafur Eliasson

The glacier melt series 1999/2019, 2019, detail (Rótarjökull)

30 C-prints, each 31 x 91 x 2.4 cm

Courtesy of the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles © 2019 Olafur Eliasson

The glacier melt series 1999/2019, 2019, 30 C-prints, each 31 x 91 x 2.4 cm, courtesy of the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles, photo: Michael Waldrep/Studio Olafur Eliasson. ©Olafur Eliasson

Amanda: Your talk with Katherine Richardson, Professor of Biological Oceanography at the University of Copenhagen, was eye-opening. Talk about the connection between your artwork and her science.

Olafur: I enjoy talking to Katherine because she has such broad insight into these issues, having worked on formulating the nine planetary boundaries, of which climate change is only one. The others are equally important, focusing on issues such as ozone depletion, biodiversity, and ocean acidification.

Katherine and I approach the issues in a different manner. I have always been more interested in science as an artist, and I seek out these conversations because I believe our two fields can add something to each other. Science often makes the mistake of thinking that data is enough to change opinions and spur action, but there is much research that suggests it is more effective to reach people on an experiential level. Art can do just that, creating a physical experience that triggers a different part of the brain, and together the two fields can drive change.

Amanda: Your work has incorporated science, architecture, history, technology, and food. How would you define your role as an artist? Do you feel it is an artist’s responsibility to address social and global issues through their work?

Olafur: I’ve always been interested in pushing the boundaries of where we expect to find art, to explore collaborations with fields that might not be used to thinking and working artistically. This interest grew out of my earlier work on dematerializing the artwork and out of experiences with works like Green river, 1998, in which I quietly dumped a non-toxic green dye in rivers at different locations around the world. Part of my engagement with the fields you mention was motivated by this desire to talk with others outside my discipline.

Olafur Eliasson, Green river, 1998, Uranine, water, Tokyo, 2001. Photo: Olafur Eliasson. Courtesy of the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles ©1998 Olafur Eliasson

Olafur Eliasson, Green river, 1998, Uranine, water, Moss, Norway, 1998. Photo: Olafur Eliasson. Courtesy of the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles ©1998 Olafur Eliasson

This desire to cross boundaries took on a new urgency when I set up the social business Little Sun with the solar engineer Frederik Ottesen. Little Sun produces affordable solar lamps for areas of the world with limited or no access to electricity, and this project got me in touch with people from many different backgrounds – especially in the advocacy world. It’s very encouraging for me to see the way an artist like myself is today invited to the table to have discussions with policy makers from the UNDP and from the EU. I think art has something special to offer these fields, since artists deal on a day-to-day level with touching and reaching people emotionally and aesthetically.

Little Sun founders Frederik Ottesen and Olafur Eliasson. ©Little Sun

Amanda: What are the most impactful things we can all do today to help protect the remaining glaciers and stop global warming?

Olafur: There are small things we can do in our daily lives to reduce our own individual footprint. As an example, I’d just cite Jonathan Safran Foer’s new book, We Are the Weather, which explains how much we can reduce our footprint simply by converting from a meat-based diet to a plant-based one, even for one meal a day! At my studio, the kitchen has transitioned to cooking primarily vegan meals after seeing the difference in carbon footprint even between a vegetarian and a vegan diet.

We’re also working on making the studio more sustainable in other ways. For my exhibition in Tokyo, for example, we shipped the vast majority of works to the museum via train and truck rather than by air. This reduced the carbon footprint considerably.

But there is only so much that businesses and individuals can do. We all need to work together and within our fields to urge those who do have power to make the changes that are needed, like instituting a carbon tax. These kind of systemic changes will have the most impact.

The Earth viewed over the South Pole

Earth perspectives, 2020. A new artwork conceived by Olafur Eliasson for Earth Day 2020, the work is part of the Serpentine Galleries’ ‘Back to Earth’ initiative—a new, multi-year project that invites artists, scientists, architects, musicians, and more to make work that responds to the climate emergency.

Amanda: You were recently appointed Goodwill Ambassador by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Discuss their sustainable development goals, and what you hope to achieve in this role.

Olafur: As a Goodwill Ambassador, I am focusing on SDGs numbers 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and 13 (Climate Action), as these relate to themes that I have dealt with in my art practice and to my work with Little Sun. I see my role as Goodwill Ambassador as having to do with raising awareness of the work that the UNDP are doing and galvanizing support for the SDGs from areas of society that may not be entirely aware of them. The Sustainable Development Goals represent a major success for international cooperation. They are the world’s best plan for facing the challenges of inequality, poverty, and the climate crisis, so more people need to know about them and work towards realizing them.

Olafur Eliasson, In real life, 2019, aluminum, color-effect filter glass (green, yellow, orange, red, pink, cyan), bulb, LED light, Diameter 208 cm, Installation view: Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, 2020. Photo: Erika Ede. Courtesy of the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles. ©Olafur Eliasson

Amanda: What is your favorite art accident?

Olafur: In my practice, one work leads to another, and there is a lot of refinement that goes into developing and finishing a project. So I don’t really see mistakes in the sense of a misspelled word or a patch of spilled paint. Rather, challenges that arise in one work lead to new research, new ideas. And even when a project is abandoned for whatever reason, the ideas can be taken up for new things. For example, in 2006 my team and I worked on a proposal for a building that was based on elliptical vaults. This project was never realized for various reasons, but the work on these forms led to a new line of investigation dealing with cylinders and ellipses that inspired Fjordenhus, the building that we began in 2009 and completed in 2018. So nothing is ever really thrown away.

At Studio Olafur Eliasson, 2013, Photo: Raphael Fischer-Dieskau/Studio Olafur Eliasson. ©Olafur Eliasson

Editor’s Note: four of Eliasson’s current exhibitions have been temporarily closed due to the pandemic. The studio and museums are discussing when the shows will reopen and closing date extensions. Information on each exhibition can be found in the links below:

Y/our Future is now, at Serralves, Porto

Symbiotic seeing, at Kunsthaus Zürich

Sometimes the river is the bridge, at MOT, Tokyo

In Real Life at the Guggenheim Bilbao