PICTURES

“Bleckner and Smith both push the notion of not just what a photograph can be, but how imagery can transcend to nearly spiritual realms.”

PICTURES, an exhibition of photo-based work by artists Ross Bleckner and Philip Smith, recently opened on Petzel Gallery’s Viewing Room platform. Curated by Ricky Lee, the show “encapsulates the artists’ shared interests in technologies of perception and the mysteries of light.”

Curator’s Dan Golden connected with Lee, Bleckner, and Smith to discuss this intriguing exhibition.

RICKY LEE

Please tell us about the exhibition and how it developed. (no pun intended)

I love photography and primarily photographic imagery that pushes the boundaries of what we think a “photo” can, should, or will be. I’ve loved Ross’s paintings ever since I first saw them in his Tribeca studio in the late 80s, during the AIDS crisis. A good friend was his studio manager, and he took me there one day, and I was moved and transfixed by their beauty. I didn’t know at the time that I would become friends with Ross and work with him professionally.

I’ve known and worked with Philip for many years. His photos operate on a spiritual and psychological level, like those of Ross. I thought it could be a gorgeous idea to invite these two artists who are from the same generation and gained acclaim around the same time to have a conversation through their art. Everything came together organically.

What would you say is the significance of art critic David Crimp’s philosophies to Bleckner and Smith’s work?

Aside from some pertinent cross-over on queer theory and AIDS activism, it seems that most remarkably, in this exhibition, one can see Crimp’s now-famous notations on representation come to life. As described in the original Pictures press release, the work “share[s] a common interest in the psychological manifestations of identifiable and highly connotative, though non-specific, imagery.”

Bleckner and Smith both push the notion of not just what a photograph can be but how imagery can transcend to nearly spiritual realms. That is the significance of being representational in feeling, not necessarily in the subject. In Crimp’s text for the 1977 show, in particular, he stated that this return to representation was one that acted “not in the familiar guise of realism, which seeks to resemble a prior existence, but as an autonomous function…it is the representation freed from the tyranny of the represented.” To me, these philosophies are apparent in the photographs from both of these painters.

The exhibition is currently available to experience solely online. What are your thoughts on this new digital-first reality?

This exhibition was initially scheduled to go on view in the physical space of a well-known photography-specific gallery in Chelsea last March. After the lockdown, this was not possible, of course. Then the trend towards online shows and OVRs emerged, and I proposed this digital version. While “Pictures” can only be viewed online right now, we have received interest from venues interested in mounting an IRL iteration, and we are considering appropriate opportunities. I think that rather than debate the pros and cons of digital versus physical, the art world should employ our creative minds and talents to develop ways in which these two viewing options can enhance each other.

ROSS BLECKNER

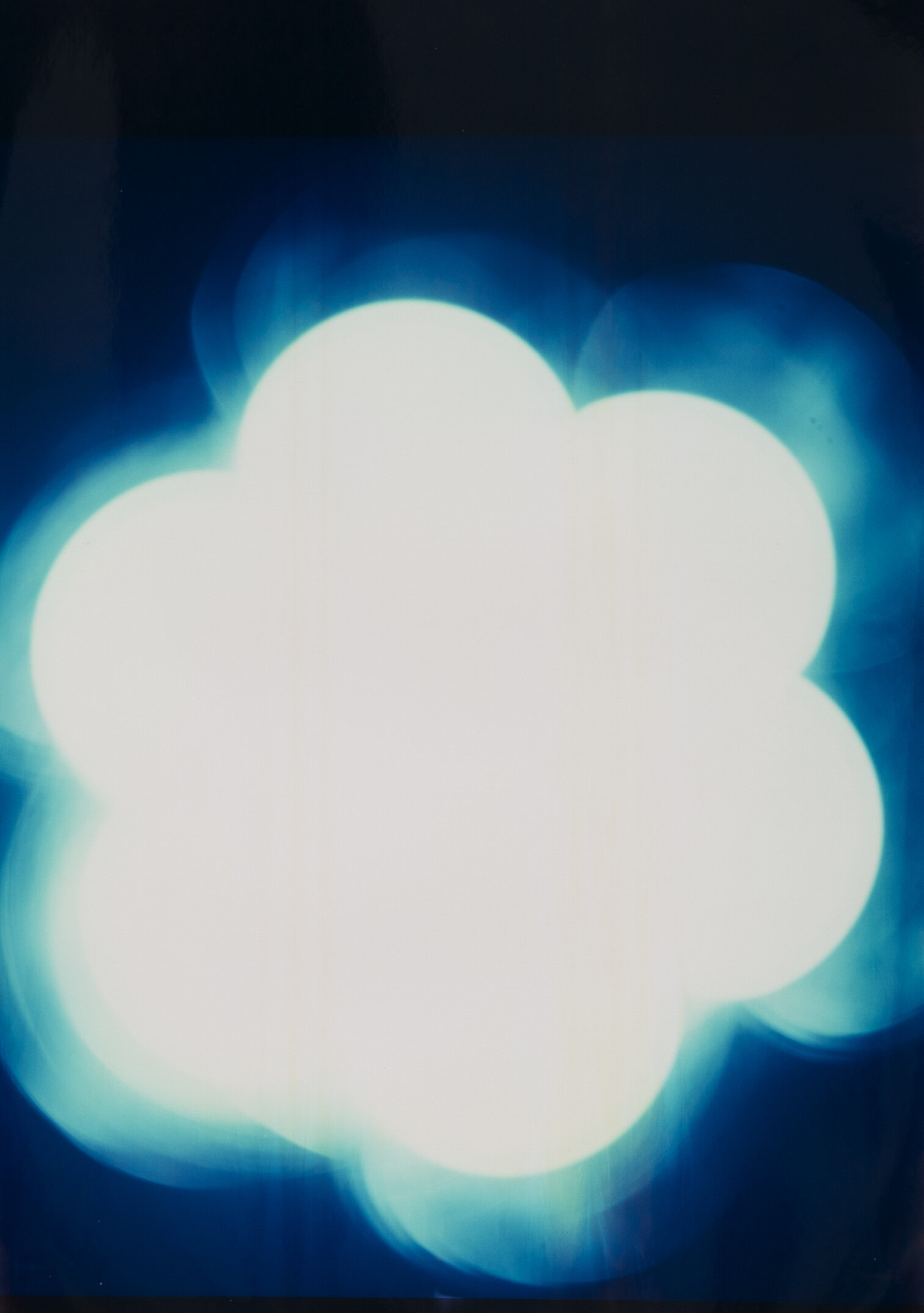

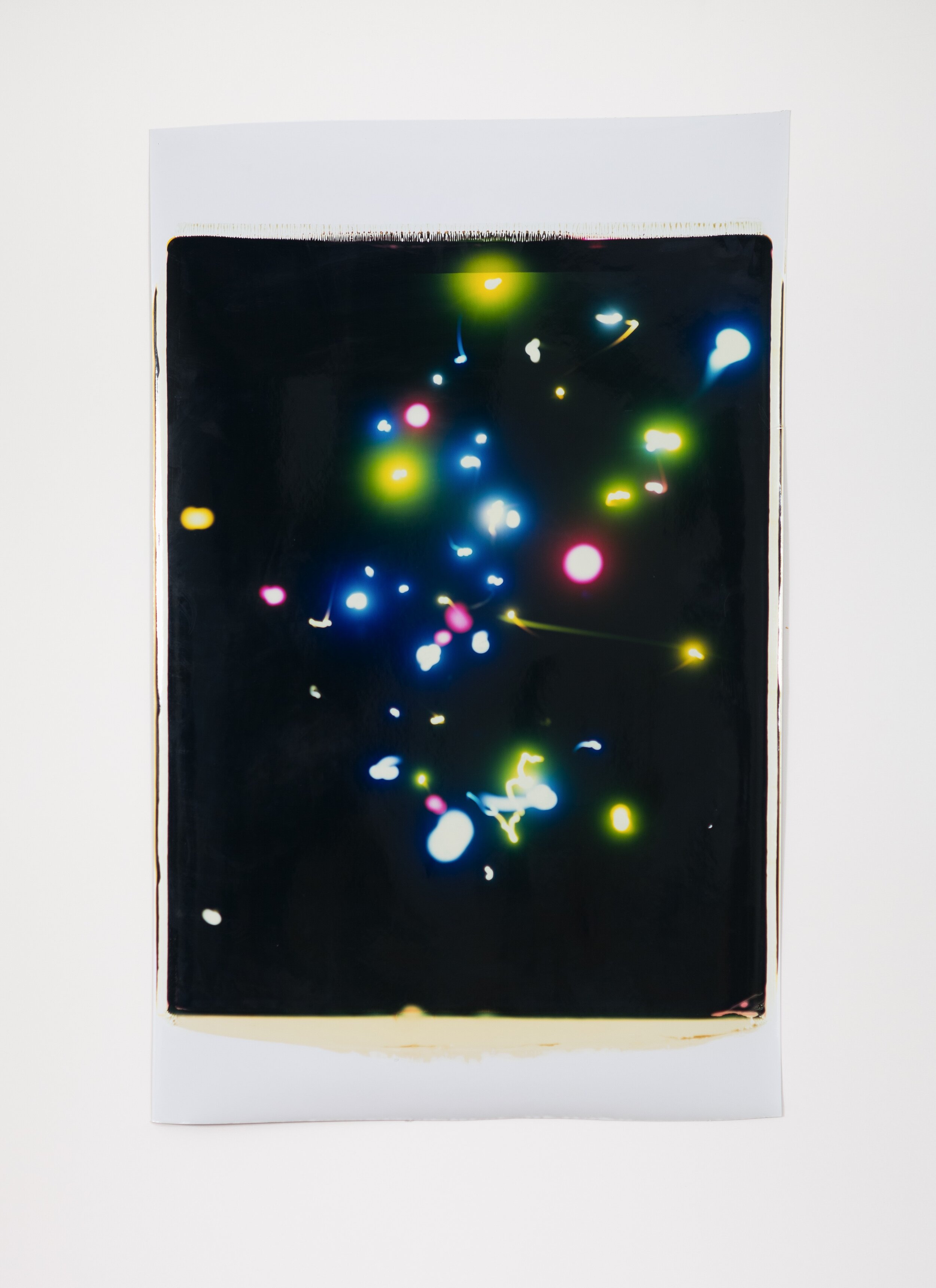

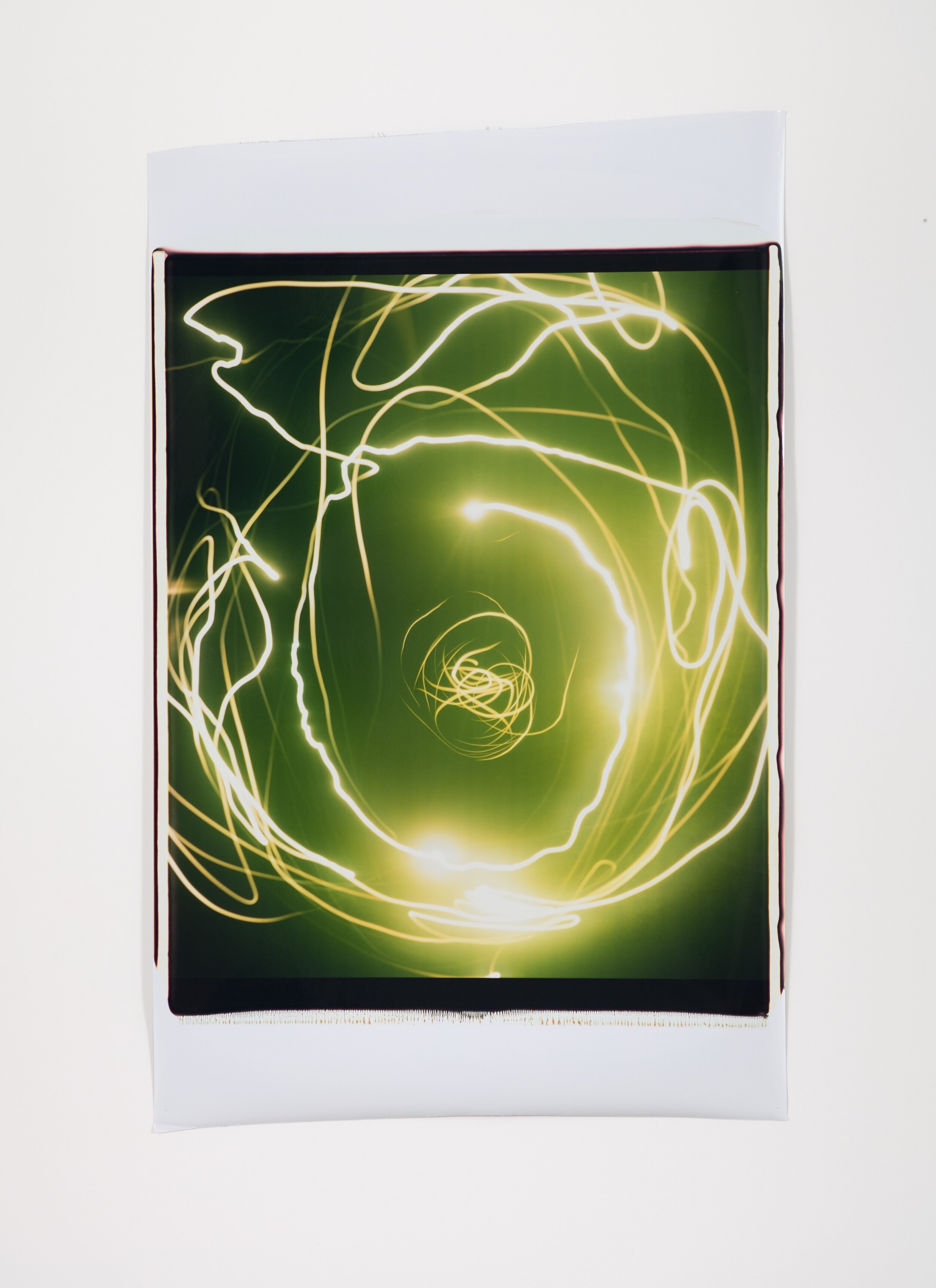

Ross Bleckner, Untitled, 2008, large format polaroid, 31 x 22 inches

Ross Bleckner, Untitled, 2008, large format polaroid, 34.5 x 22 inches

Ross Bleckner, Untitled, 2008, large format polaroid 34.5 x 22 inches

Ross Bleckner, Untitled, 2008, large format polaroid, 34.5 x 22 inches

“I like things that are mesmerizing, hypnotic, and phenomenological. ”

What drew you to using a large-scale Polaroid camera as part of your creative process?

I love long exposures, light, and all its physical and metaphorical definitions. I like things that are mesmerizing, hypnotic, and phenomenological. I also like the idea that the camera’s function is to create an image from light capture.

A fashion magazine asked me to do a shoot, and the camera they had in the office was a large-format Polaroid. There are only a few left in the world, and one of them happened to be there. After the shoot, I had use of the camera for half a day. I went to the Bowery and bought a number of light sources which I moved in front of the camera to create different configurations. It seemed like the perfect opportunity to join the Polaroid's immediacy, capturing light with the image of light itself.

“Light” and “Mystery” come to mind when looking at your entire body of work. What do those words mean to you?

To try to somehow represent the light in, through, and from the inextricable connection between us as each other and us as part of nature, as humbling and elusive as it has been this past year. It is the mystery that hopefully gets captured in moments in an artist’s practice.

Are there things you can achieve through this photographic approach that you are not able to through painting, and vice versa?

A photograph can replicate more directly what the camera is "exposing.” Painting is an ineffable accumulation of the experience of an image.

PHILIP SMITH

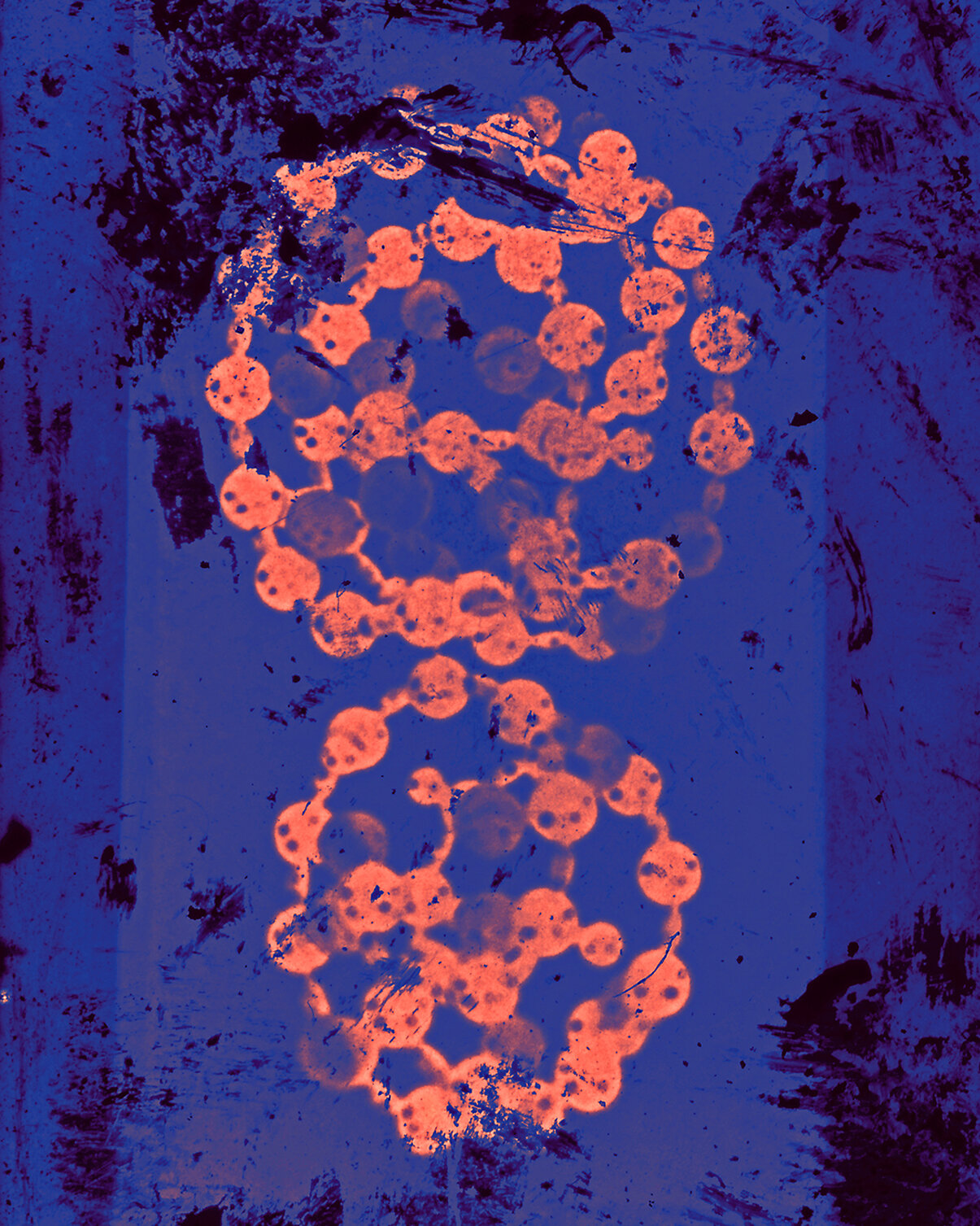

Philip Smith, Proton, 2020, 35mm film negatives printed on watercolor paper, 63 x 43 inches

Philip Smith, Spinners, 2016, 35mm film negatives printed on watercolor paper, 63 x 43 inches

Philip Smith, Globe 1, 2020, 35mm film negatives printed on watercolor paper, 63 x 43 inches

Philip Smith, Physics 3, 2020, 35mm film negatives printed on watercolor paper, 63 x 43 inches

“I want the images to take the viewer somewhere other than where they are.”

What draws you to the source materials you use?

I’m attracted to images that can mean something other than what they represent at first glance. They should have an initial oddity that catches me off guard. If I had to categorize the images, I would say I’m interested in pictures that hover somewhere between science, metaphysics, and complete absurdity. Also, they can’t be too recognizable or too contemporary. Maybe just familiar enough to lure you in but unlike anything you’ve ever seen before. I want the images to take the viewer somewhere other than where they are.

Can you share a bit about your process?

My process is sheer stupidity and accident.

In the early 70s, I started taking pictures with a beat-up camera using black and white film. This allowed me to sneak into bookstores, museums, libraries, or anywhere and capture images I liked without having to buy an expensive book. I would go home and pretend I knew how to develop film, which I didn’t, so the negatives would emerge with all different densities—some too light and some too dark.

One day Jamie Nares stopped by the studio to have a look and saw all these negatives strewn all over the place. He asked what they were and I explained they were reference material for my paintings. Brilliantly, he suggested that I should print them. I never thought about it since they were just my library of images.

Years later I remembered his comment and thought, “Hmmm, I live in the modern era with all kinds of technology, let me try and scan these and see what happens.” Now, these poor negatives had gobs of paint of them and were basically abused by me in the studio. Since they weren’t a nice flat piece of paper, the scanner had a bit of an issue dealing with all the unevenness of the negative and the gobs of paint so the scans were less than perfect.

As a test, I sent a bunch of these scans off to the drugstore to see what came back. Initially, I was horrified that they looked like someone had slipped the scanner some LSD, they were very trippy. The more I looked, I realized they were unlike anything I had seen before, especially in a photograph.

You welcome scratches, tears, and patina in your work. What appeals to you about these imperfections?

Yes, they have a wabi-sabi feel to them. The damage, the imperfections are part of their innate being and beauty. They result in something more painterly than photographic with layers of history. In many ways, they are like artifacts that have been unearthed. In part, due to their lack of photographic perfection, the images are more like manifestations in that they just appear from some unknown dimension.

As I said to Ross when we discussed the show, you can tell by looking at his photographs that only a painter could have made them. His photographs invite chance, randomness, and lack of control. I believe those words apply to my photographs as well.

What is the significance of scale to you and your work? (both the actual size of your works that pull from small, 35mm slides, and the elements you reference, such as molecules)

The scale is important, it gives them a presence. When we print a small test, maybe 6x9 inches, they feel like small botanical drawings from another time. There is a preciousness to them, unlike the final printed photographs which are five feet tall. This gives them a somewhat totemic quality. They tower over the viewer. I look at them as sentinels guarding the viewer like those mythical figures guarding the gates in ancient Babylon.

This show references Pictures, an exhibition you were a part of in 1977, curated by art historian Douglas Crimp. What would you say are the correlations between the work you shared in that earlier exhibition and this one?

Same but different. In my mind, there is no difference between the work back then and now even though it has continually evolved. It’s all of a piece.

I’m still interested in creating a pictographic language. Images are so powerful, they have been since pre-historic and pre-literate times. When I was in my twenties, I remember standing in Egyptian and Indian temples in utter awe of the mysterious images that surrounded and overwhelmed me.

In martial arts, the term ren ma refers to polishing and refining your technique. It’s like you take a rock from the ground and polish and polish until you end up with a glittering gem. In some ways, I’m still polishing that rock from 1971 into a gem.

I wish Douglas was here, it would be interesting to hear his response.

Ross Bleckner portrait courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York.

Philip Smith portrait courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York.

Ross Bleckner & Philip Smith PICTURES is currently on view at Petzel Gallery’s Viewing Room